David Lowery’s AIN’T THEM BODIES SAINTS is a strong silent type of movie, a Lone Star noir full of the unspoken feelings of decent people and the stoic acceptance of what men and women must do when faced with the consequences of their actions. There is more than a touch of nostalgia about it, of a period slightly bygone, sometime in the ’70s, perhaps, but with sensibilities that persist to this day, as surely as the ravaged buildings of the Texas town, Meridien, that is the center of its drama. Sunset and dawn bracket the night in this film; there is daylight too, but never a high noon.

The persons of the story know those days are past, if they ever were, and that survival is more about flight and concealment than a head-on confrontation on Main Street. Bob and Ruth are lovers, but not violent souls, even though a crime is committed and Ruth has a protector, Skerritt, who talks down those who threaten her with his own threats, and backs them up with a gun. There’s a lawman who has a hankering for Ruth, and gets on with her daughter, but is honest in his job, and a loyal saloon keeper called Sweetie who gives shelter to Bob but is uneasy about doing so. These are all people who are torn but do what they must at any given time. When they talk of the future it is more about staying put or getting out of danger than improving their lot. These are those the dream never touched, living the lives handed to them with the dignity of stones, ineluctable as the rise and fall of the sun.

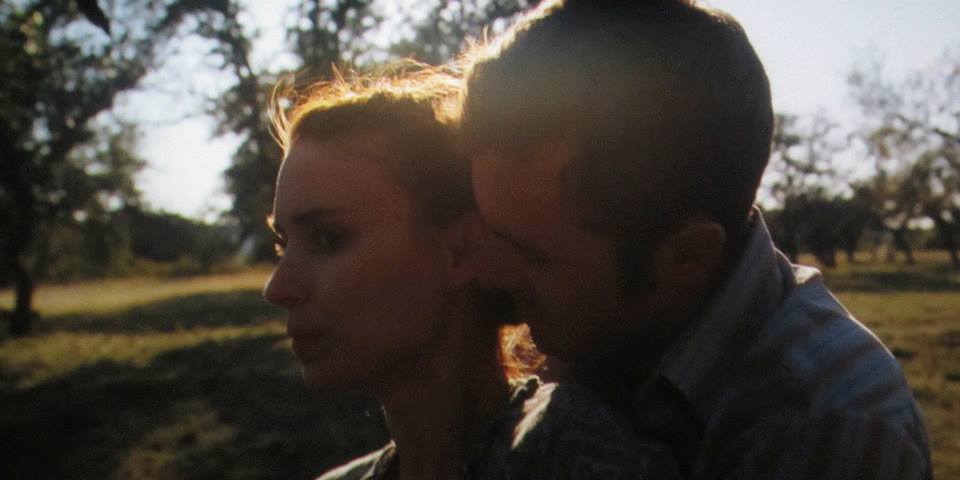

There’s a lot of Terrence Malick in AIN’T THEM BODIES SAINTS, in both its plots and its shots, plenty of Bonnie and Clyde (but without the malice), and an allusion to Sergio Leone in the form of three sweaty gunmen who show up at Skerritt’s store. Keith Carradine was born to age into such roles as Skerritt (and to sing such songs as “The Lights,” which closes the final credits). The film is, in general, blessed in its actors. Something in Casey Affleck’s face conveys the torture of a trapped soul who knows both love and desperation; the young outlaw Bob could have no finer an interpreter. Rooney Mara is his lover Ruth, and I mean that almost literally. That is who she is for film’s 96 minutes, and whom we get to know. Or try to, for what Mara understands as few performers do is the inscrutability of human beings and the elusiveness of the selves she portrays.

Check listings for viewing options.