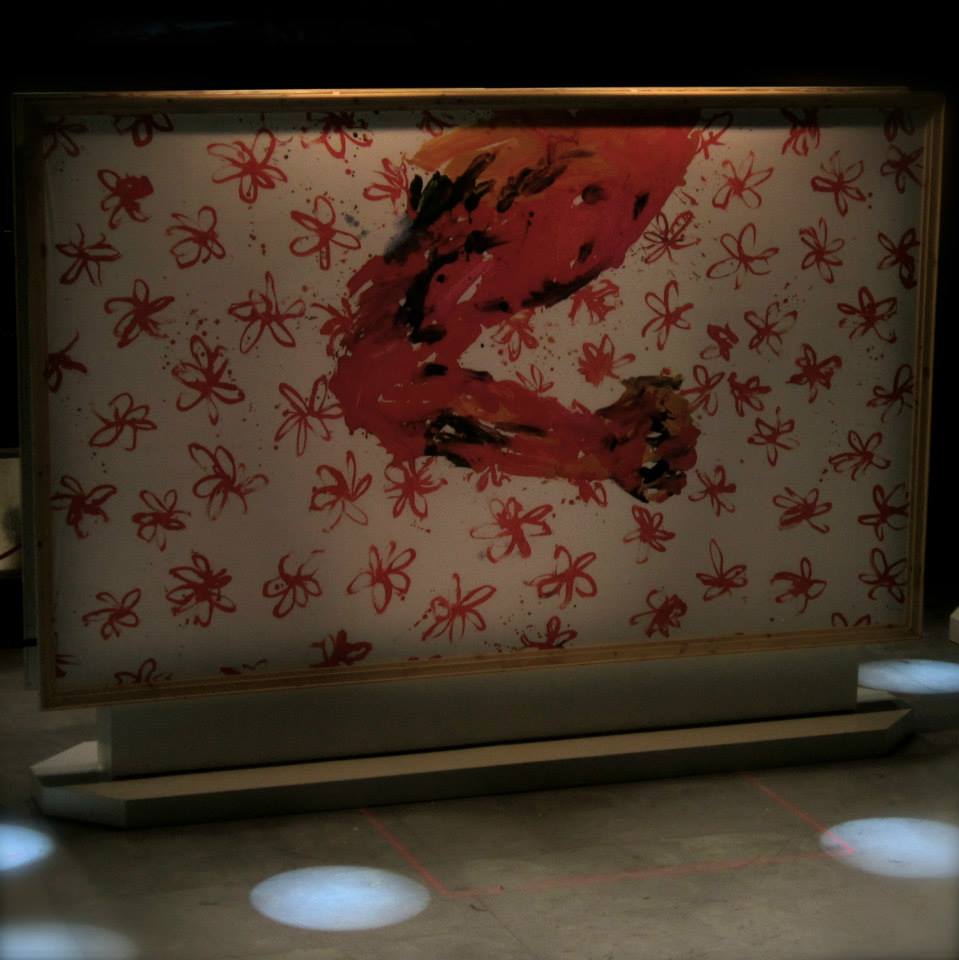

The first of four pieces in BADEN-BADEN 1927, Gotham Chamber Opera‘s update and reassessment of the German spa-town festival held in that year, is Milhaud’s “Abduction (or Rape) of Europa.” It happens in front of a picture by the contemporary artist Georg Baselitz, who is known for exploring identical images in multiple works and from different angles. The program has the same image on its cover as one sees on the stage, but tipped on its side with the elbow pointed up. In the opera itself, one of the characters appears in a suit that replicates the patterns of the design and sometimes fits over it like a transparency on a projection screen.

The point of the original festival, curated (in today’s parlance) by Paul Hindemith, was to explore the question, “What is Art?” Just having learned of the death of the critic Arthur Danto, a champion of conceptual art, I am tempted to wonder if the original Baden-Baden, even with opera as its medium, might have qualified as such. The Gotham version certainly does, with its keepsake program and installation art designs, interspersed with theatricalized lectures that interact with the audience and sometimes bring its members onto the stage (thus asking the secondary question, “Who is the artist?”). The conceptual fascination of this goes a long way, and each piece approaches two or more artistic media in a way that asks how far each can interpenetrate the other.

To what extent, “The Abduction of Europa” seems to ask, can the Baselitz image replace the Titian masterwork with which the Milhaud shares its name, and how far can its imagery spill across both the characters and, via the programs in their hands, the audience? In Toch’s “Princess and the Pea,” about a bride chosen simply for her sensitivity to a bump under a mattress, the unifying conception is reality television, which makes people famous for insignificant reasons. (It is no accident that such approaches to staging, rarer once than they are today, used to be called “concept productions.”) All the while the music is asking itself what the nature of a pleasing sound is, whether it can carry a dramatic narrative, and so on. Hindemith’s own “There and Back” gets right at the nature of dramatic structure, a delightful little opera that spins out a murder-suicide and then reverses the action until everyone is alive and well again. It asks, I suppose, what is tragedy? and is the tragic ending really inevitable? Finally, the Brecht-Weill “Mahagonny Songspiel” is staged as an installation in a museum entitled “Treadmills,” which leads to an entertaining metaphor: capitalism as a long forced walk that gets the average person nowhere. It is not surprising that the Weill songs proved to be the most theater worthy of the evening. Whether Hindemith knew it or not, including a composer with so sure a popular touch may not have answered the question “What is art?”, but it certainly asked what its function is and for whom it is being produced.

I found the last two pieces of BADEN BADEN 1927 to be outright rousing, both intellectually and theatrically. Of the first two, the Milhaud was over quickly, but provocative; the reality show parsing of the Toch, a little much. That I have said nothing yet about the performers and musicians is indicative of how much the conceptual tone dominates the evening: the more vital the concept the more compelling are its messengers, but good work all around. There’s one more showing on Tuesday night.

Click here for information on Gotham Chamber Opera programs and events.

One response to “Baden-Baden”

[…] here for information on Gotham Chamber Opera programs and […]