The plays and dramatis personae of Tennessee Williams are basically abstractions of emotions and other states of being. Stanley and Blanche are masculinity and femininity abstracted; in a very real sense they are detached qualities rather than people, even in the limited sense that fictional creations aspire to be. I think of the dreamy sentimentality of The Glass Menagerie, the aestheticized savagery of Suddenly Last Summer, the not quite real guilt and decay of Night of the Iguana. The very title of CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF – now in revival on Broadway – is an abstraction of unsatiated desire, and when the persons of the play invoke the image, it is not as metaphor but simile. Brick and Maggie simulate frustrated homo- and heterosexual libido, and Big Daddy its craven satisfaction, but no one really embodies it. They are melodramatic forces rather than naturalist souls.

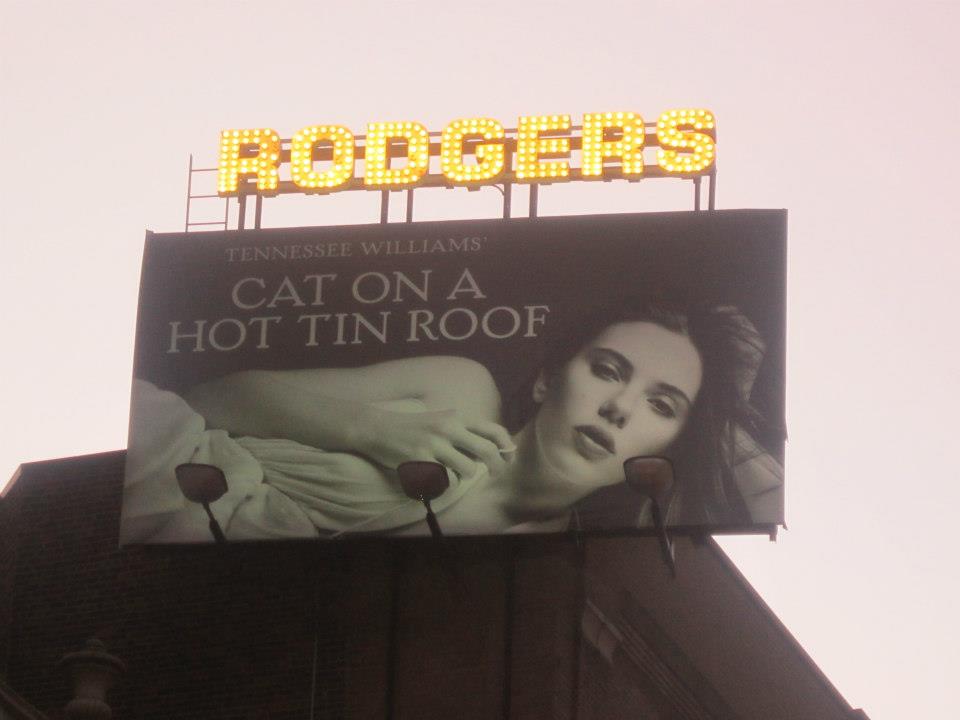

This might be taken as a damning criticism of Williams, but if one takes the plays for what they are, which is as poetic melodrama in the drag of mid-century American Naturalism, then it ought rather to explain what makes them distinctive and original. Rob Ashford’s production is satisfying precisely because it states and never hides the emotional states it abstracts, horniness unsatisfied, and the related desire for parenthood. Maggie is played by one of the screen’s preeminent sex symbols, Scarlett Johansson, who has aroused the itch in tens of thousands of moviegoers, but who has such integrity in the theater as to make one forget the underlying psychology of the casting. She dominates the stage to the extent that you have to get used to it every time she exits, but not because she hogs the scene or plays the celebrity card (on the contrary, she is the most matter-of-factly easy movie star to be in the same theater with I have ever encountered). The only problem with her as Maggie is her obvious fitness (I doubt that Maggie exercises or eats healthy food, whereas Johansson clearly does), but everything else about her is right for Maggie, unless one feels that she should be somehow dislikable, which Johansson is not. Johansson’s Maggie is by far the most sympathetic figure in the drama, more so even than her husband Brick, whose lack of interest in her (in Scarlett Johansson, mind you) is due to the repression of his own sexuality by the society around him.

That could be a basis for Naturalism, but this is Williams, so it is over-the-top melodrama instead, with thunderstorms moving in at dramatic moments, and the tin roof simile, and Big Daddy’s cancer coming to a head at just same time as the sexual frustrations of the marriage. Something in the South lends itself to the melodramatic imagination, in which every moment is filled with emotional significance, and despite its excess, there are truths to be had because of it, boils to lance on the Id of the culture. The conflict between Brick (Benjamin Walker) and Big Daddy (Ciarán Hinds) is much in this mode, son and father, analysand and analyst, the Oedipal figure as doctor. Johansson is reason enough to go, but the climax of the father-son confrontation is worth it too; the melodrama comes as near to the truly human as it can without actually getting there. It would be a mistake to do so, for that would not be Williams’ world, or the world he saw, which is the one in which we live.

For more information, click here.