There is much greatness in the visual art of the United States, but in the end I always settle on Hopper. I went away from Modern Life, the Whitney Museum of American Art‘s 2013 retrospective, thinking his paintings, which teeter on the line between the beauty of solitude and the pangs of loneliness, to be the wisest we have produced. He saw quite clearly what transpires in American life under the boosterism, the talk of the Dream, the myth of the individual. He knew the shadow next to the light, and its inexorable lengthening.

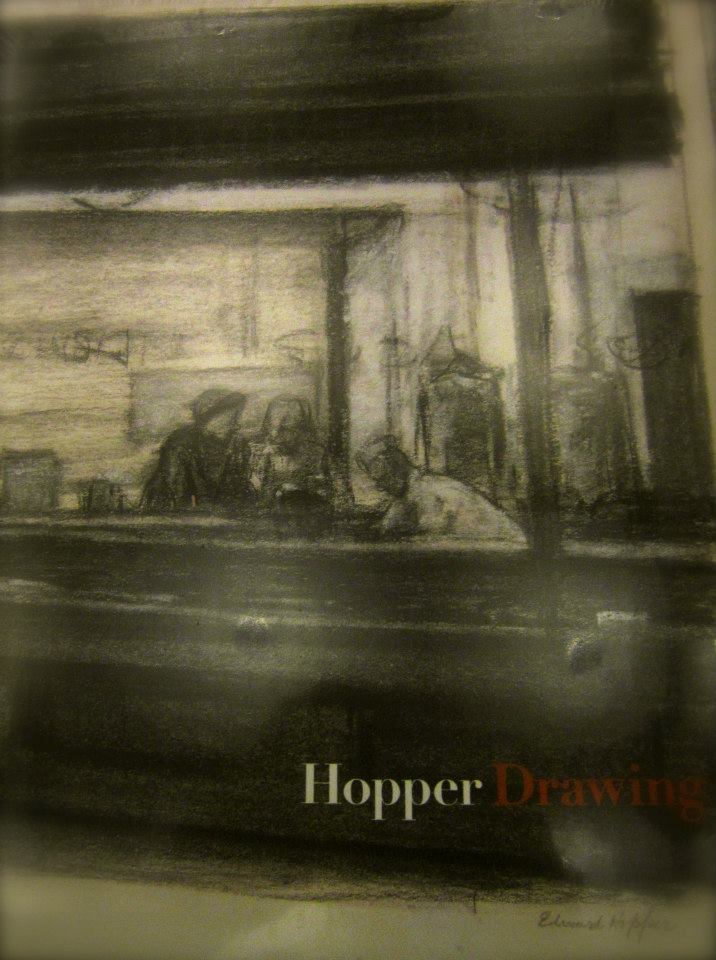

So I was drawn to the Whitney’s HOPPER DRAWING, even though my interest in exhibits of preliminary sketches and other auxiliary artifacts is somewhat limited. This isn’t a judgment, merely an exercise of personal taste: the force of the final product interests me more than the minutiae of the process that led to it. But the Whitney exhibit, of the preparatory drawings astride the products they led to, is genuinely illuminating of both the process and its results. The sketches are solid and expertly crafted, documentary in their precision and observational acuity; but then one sees that in the paintings the subjects of the drawings have been hollowed out, not of their essential substance but of all that conceals it.

Hopper is quintessential to the dominant culture of the U.S. not because he portrays its myths but because he intuits their falsity. He recognizes as did Thoreau a perverse strain of individualism that, unlike its counterpart in European Romanticism, regards the other as an impediment rather than as a friend or ally who might share in or contribute to the vision of the adventurer. The achiever wallows in the fruits of his accomplishment, or in the rot of his failure, destroying in his mind the contrary culture that surrounds him (the male pronoun feels appropriate here), and for himself effects, as it were, the status of the last man on earth.

The New York of Edward Hopper is a depopulated city in whose streets, offices, diners and bedrooms the survivors clump, or stand, or sit utterly alone, in the abstemious light of the void. The roads they take out of the city are empty even of cars, much less of pedestrians, and the windows of the inns in which they seek lodging display nothing but furniture. The cumulative power of Hopper’s work has never been so apparent to me as in this show. The quiet desperation that those who have grown up honest in this country must acknowledge as its defining trait falls like a shadow on the few, the unhappy few, be they within the frame that Hopper has delimited, or outside of it gazing in.

Click on Whitney Museum of American Art for information on current and upcoming programs and exhibits.