Yael Faber’s MIES JULIE, which adapts the Strindberg play to what is bitterly described as “the new South Africa”, is a raw, explicit, and sanguinary baring of a national soul. The white Julie, whose class has ostensibly been defeated, still has her sexual encounter with John (the “Jean” of the original), whose class – and African race – has ostensibly won its majoritarian birthright. But the ancestral oppressions remain, and with them the perverse overlaps of sex, power and violence that give the Swedish source play its peculiar and enduring power: there will always be a Hegelian dynamic between lord and bondsman, in which the first holds the formal power and the second an ironic and morally potent counter-power in that he, or she, can deprive the lord of the servitude upon which his – or her – identity depends.

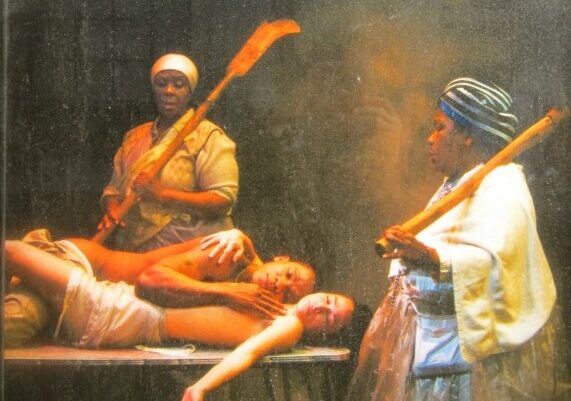

This retooled version of Julie leaves a stain upon the St. Anne’s Warehouse stage that is as indelible in the memory as the blood on the hands of Macbeth’s wife. It begins by stripping the setting of its Nordic charm. The kitchen is not a cozy redoubt, but located in a squalid hovel to which the “liberated” Jean is still relegated (along with his mother, who replaces Christine, his fiancée in the original), and which was built on the graves of his ancestors, one of whose spirits is hauntingly present; the animistic roots of an ancient tree threaten to break through the tiled floor of the habitat. The quaintly pagan celebration of Midsummer Eve is replaced by miserable heat and an unnamed African festivity that, unlike in Miss Julie, never invades the stage. It doesn’t need to, because, whereas in Strindberg, it drives Jean and Julie into an anteroom where their passion is consummated, in MIES JULIE we see the act, which as portrayed is tantamount to rape. Strindberg’s drama has always had this potential – this is not the first time I have seen the sex brought violently into the open, nor that the trappings of the Swedish aristocracy have been replaced by an even more exploitative power structure that turns sadistically on its wielders.

The traces of aristocracy that remain (such as the notion that Julie went to boarding school and has a pet bird in a cage) are not totally convincing here; this is a guilt ridden Julie, with little pretension to her own legitimacy. Hilda Cronje’s performance is a courageous tour de force of pain, lust, self-loathing, and the psychology of attraction and repulsion that sexualizes racism at its worst. At the curtain call on the day I attended, the equally brave Bongile Mantsai, who plays John, managed to prompt a smile from Cronje, who until then had stood as though stricken by the power and self-revelation of her own performance.

For information about upcoming events at St. Ann’s Warehouse, click here.