I think that I have never seen a Miss Julie quite like Chulpan Khamatova’s. It’s not just that Thomas Ostermeier, the director, and Mikhail Durnenkov, the adapter, have updated and transposed Strindberg’s 1888 original, making Julie the spoiled daughter of a Russian general rather than a Swedish count, the celebration of New Year’s instead of Midsummer’s Eve, the period not 19th century but present day. It’s that Khamatova finds in everything that doesn’t make sense about the transposition a completely new psychological shape to a signal role of the world theater. Rather than a young woman who deteriorates over the course of a very bad party, Khamatova’s Julie, out of the erratic emotions of the night, makes herself whole, however tragic the end may be, a move from weakness to strength, fecklessness to responsibility, frivolity to enlightenment.

I realized, watching her, that, however powerfully performed, Miss Julie doesn’t end, as a rule, by generating much sympathy for the title character. This is partly due to Strindberg’s well-known pathologies in respect to women, but also because the drama is so intricately structured as symbolic tragedy. Julie’s fate, in the original, embodies a complex of sex, class, gender, and history by which she and Jean, the servant she beds, are caught up and destroyed. Exactly who seduces and exerts power over the other is exquisitely dialectical, but they are in the upshot objects in a deterministic system, and the ends they come to, or look toward, are more likely to prompt a sense of being “for the best” or “it had to be” than real human empathy.

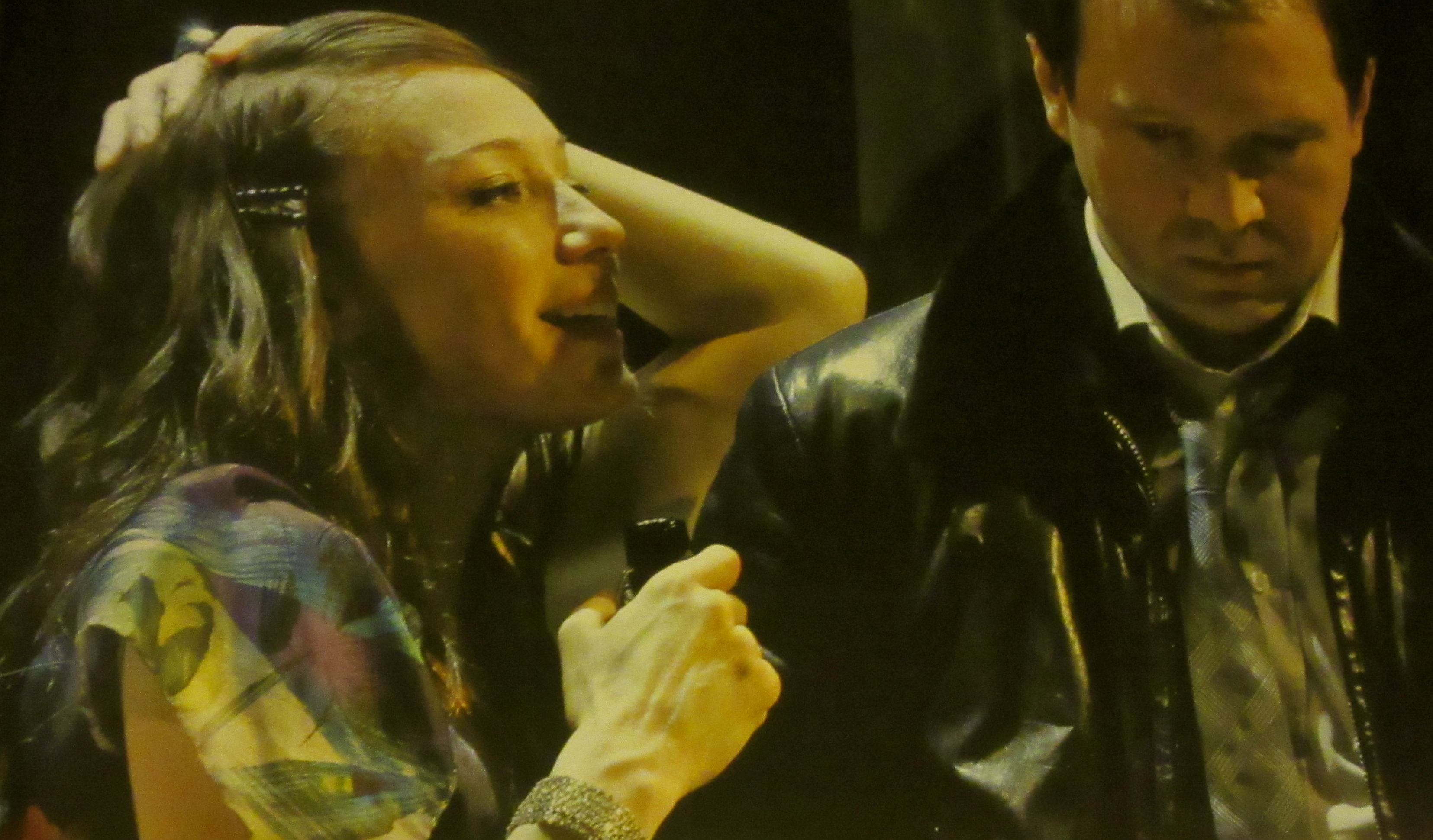

Not so Khamatova’s Julie. It was like seeing someone grow up before my eyes. She turns from a flirty, attractive, but shallow, not very likeable person to an actualized, self-aware human being. The drama is about her, as a person, in a way that I have not experienced before. Khamatova makes a Julie who can be sympathized with if not admired for the realizations she comes to, and Ostermeier-Durnenkov’s version of the play adjusts to this reality in the ambiguous imagery of its denouement. Jean is for once, in the event, not the quasi-victor in the struggle and doesn’t, in Evgeny Mironov’s thuggish interpretation, evince the empathy he usually does, as one aspiring to independence but hypnotized by class. Mironov’s chauffeur is, instead, part of the problem, an ex-soldier enacting the violence of war in domestic relations, the hubris of conquest in his fantasies of the future.

The housekeeper Christine, ostensibly engaged to Jean, is a strong presence in this version, which is good to see. Strindberg’s stated conception of the character is that she is a creature of pure convention, unlike Julie and Jean, who are motivationally complicated. In fact there is something indomitable about her, at its core compellingly human. Switching the play to the present, the social and religious verities Strindberg shackled her with having dissipated, helps. So, most of all, does Julia Peresild, who is as memorable in the role as Khamatova in hers. There is a fire at first controlled in her, that smoulders, then blazes, when the fuel is poured.

Ostermeier’s staging is beautiful to watch, from the gleaming post-modernism of the kitchen to the confetti-like accumulation of snow, first on the edges, then working its way in. The adaptation retains a lot of the original dialogue, and the psychology behind it. Much of it, particularly as regards to sex, seems out-dated to me, especially given the jet-setty, oligarchical culture that Julie moves in, although it must be granted that tradition holds strong in unexpected places. In the end, what doesn’t seem right in the transposition is psychologically generative. Khamatova’s Julie moves in an emotionally confusing world and the less sense it makes the more powerful, oddly enough, are the realizations to which she comes.

Lincoln Center Festival presents the Moscow-based Theatre of Nations’ MISS JULIE through Aug. 2 at New York City Center.