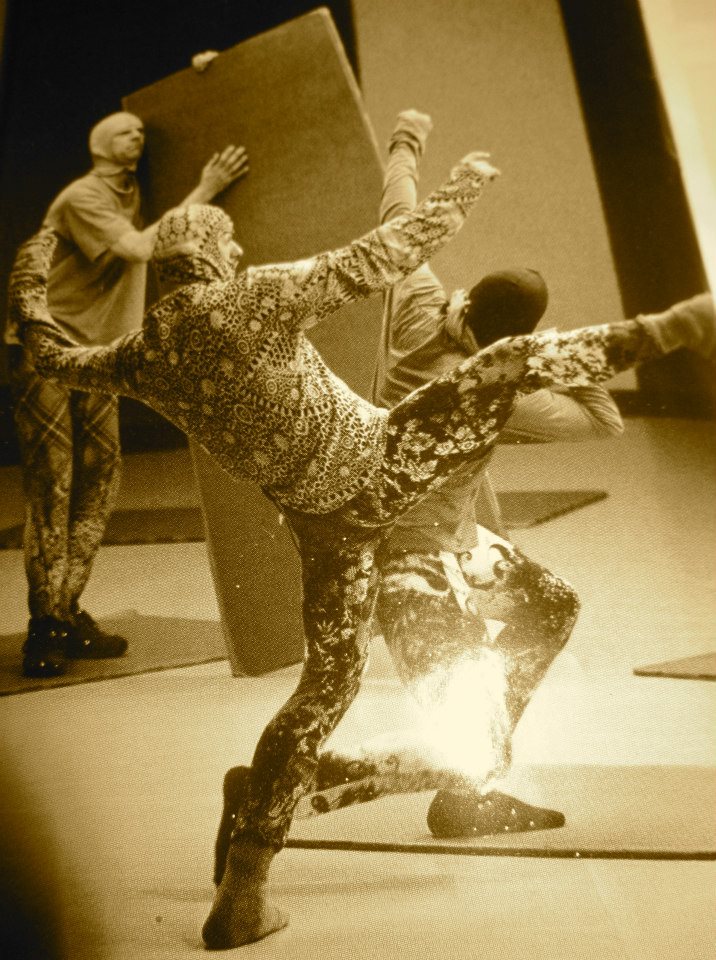

SIDER is a dance performed to the soundtrack of a film of an unspecified Elizabethan tragedy that the dancers hear through earpieces but that the audience does not. There is other sound and musical accompaniment that we do hear, including vocalizations, which do not seem to me to be in a particular language, although I may have missed something on Wednesday night since the company, while headed by an American, is based in Germany. The bare stage is illuminated by tubular lighting units overhead; the only properties are large rectangles of cardboard, a few decorated with cryptic slogans (which neither sound like nor ring any bells as coming from an Elizabethan text). The dress is mostly modern, but with period allusions, such as peasant caps on the men and the occasional stiff lace collar.

On one level the piece is a kind of game. It’s hard not to speculate on what tragedy is being listened to, although it is also made clear that the dance is not supposed to be an interpretation of the unnamed work, merely something traced upon the palimpsest of its vocal patterns, just as there have been dances based on fractals or algorithms. The 70-minute running time is also vexing if one tries to guess the play, as few works of such brevity come readily to mind, filmed or otherwise (and no, I have not gone on an obsessive search for what it might be). Of course they may be listening to only part of the screenplay or to one that truncates the text – there is no way of knowing. One thinks first of Shakespeare, of course, then of Marlowe, then, perhaps, of Middleton and Tourneur, as there is at least one film of THE REVENGER’S TRAGEDY, and then one gives up, beyond making the stray connection as the piece proceeds.

The choreographer is William Forsythe, and the company is the one that bears his name, and the venue is the Brooklyn Academy of Music. It is best to go to SIDER alert and well-rested, as drifting off on its hidden and sedately repetitive rhythms is all too easy, despite the flurries of group activity and consistently piquant footwork. The effect is spare and seemingly without plot, despite the dramatic source, but there are certain moments that seem characterological, and others that look scenographic, due to a confluence of period touches in the costumes, or when the cardboard is organized into architectural structures. The many dancers are lithe and exceptionally nimble, with presence and charisma, and I did leave feeling that I had brushed up against something of the past strangely filtered through the modern.

I think, by the way, that the film is of a Shakespeare text, edited down and perhaps short to begin with. MACBETH would fit the bill. But I really have no way of knowing.