I came to Norman Lindsay’s witty, wise and wily novel AGE OF CONSENT through the effervescent film of the same name that the great Michael Powell directed in 1969.

Some have spotted a connection to Shakespeare’s The Tempest in the plot, which concerns a painter struggling to find inspiration on an isolated Australian isle accompanied by an Ariel-like dog and encountering a teenaged girl who becomes both model and muse. Until the painter’s arrival, the girl (a sort of amalgam of Ariel and Miranda) has been raised in cruel isolation by a guardian who is continually compared to a witch (making her the Sycorax figure). There is also an attempted violation of the girl by a brutish local, which is a possible echo of Caliban’s attempt on Miranda in Shakespeare’s play. Truth to tell, the Shakespearean parallels feel a little tenuous, as easy as it is to express them, and I have no idea if they were intentional or not on the part of the novelist. I do believe that Powell thought they were there and that his film, in turn, influenced Paul Mazursky’s 1982 modernization of the Shakespeare play.

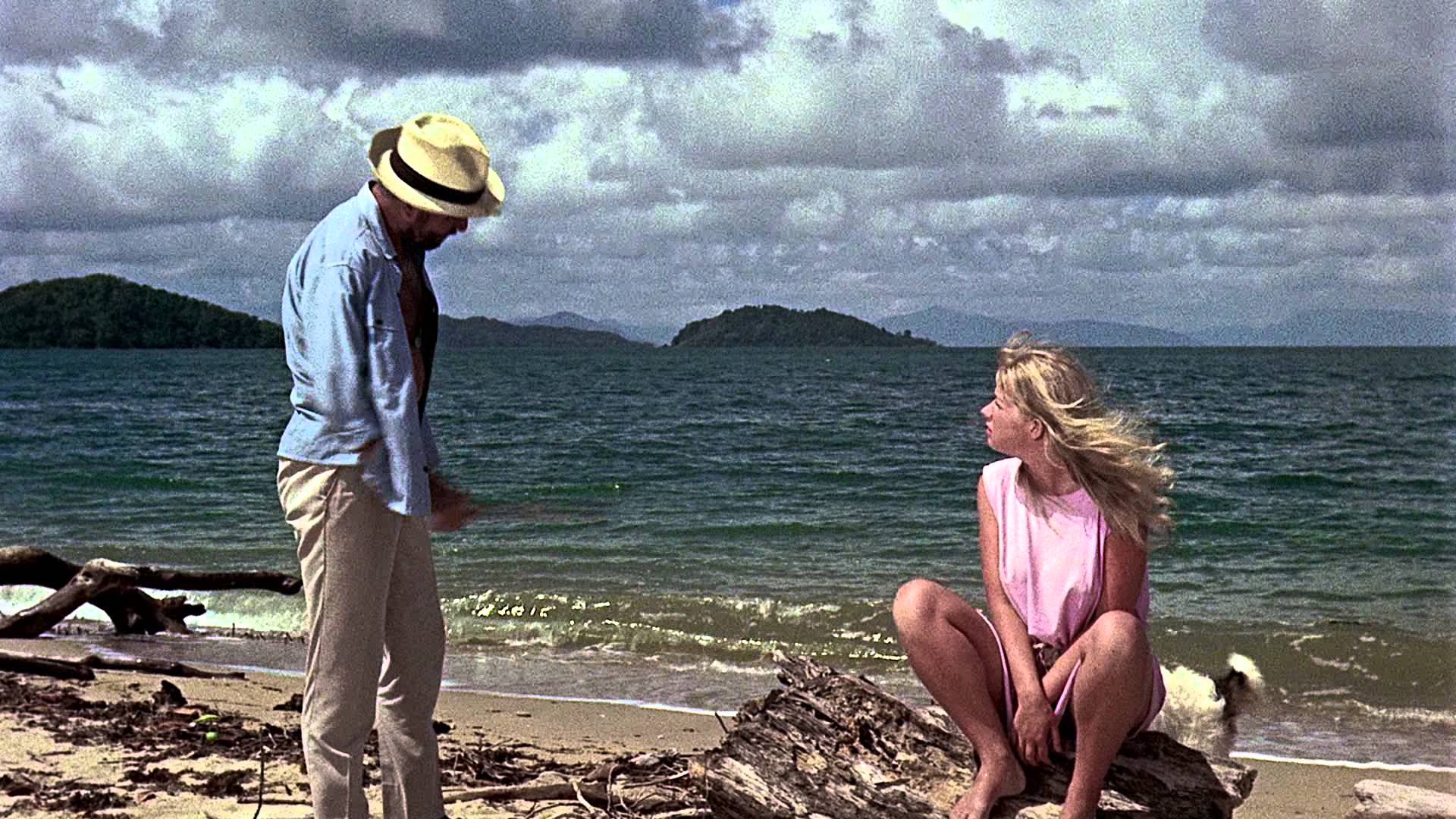

Be all that as it may, this is one of those unaccountably obscure novels that ought never to be out-of-print, yet is. The author was himself a notable painter, and his mastery of the craft informs his portrayal of the protagonist’s creative struggles and is also apparent in the delightful illustrations he did for the book itself. Not the least of the novel’s pleasures, if you know the film, is the realization of just how perfectly cast the young Helen Mirren was as the girl, to say nothing of the brilliance with which Powell and his leading man James Mason transformed Lindsay’s cozily readable prose into a work of languid cinematic ecstasy. The film and the novel are different in many respects (including the time periods they are set in), yet they are clearly of a piece, and I heartily recommend them both, in either order.

Mirren, interestingly, went on to play the Prospero figure in Julie Taymor’s film of THE TEMPEST, which, from “our revels now are ended” on, won me over with its dark vision, particularly through the bitter post-colonial gaze of Caliban on his final exit. It took until then, I think, because the grimness of the ending is over-anticipated in the preceding scenes. The acting is excellent, although Mirren, perhaps to empower Prosper-ah as a woman, eschews the petulance that the part, originally Prosper-oh, has ideally, and which Mason as Lindsay’s Prospero-esque alter ego had in fact.

Check listings for viewing options.