Brian Dennehy, who plays Larry in the Goodman Theatre’s THE ICEMAN COMETH at BAM, is the sort of actor who gets you imagining in advance what he will be like. Metaphors involving hulking animals form before their time. He will sulk like a defeated bear, howl like a yeti, hang his arms like an ape. None of which, in the event, is wrong. His is a mammoth presence on the verge of extinction. But, for all his grizzly power and simian strength, he mostly just sits there, on the edge of the scene, and gazes outward, somewhere in our direction, over our shoulders, or through the back of the house.

There is figure in Renaissance art for which there is a technical term that I haven’t managed to track down for this writing. He – the examples I recall are men – looks away from the action on which the other persons of the visual drama are focused, beyond the frame of the artwork, at someone or something, an implied person or event that concerns him. The gaze of the looker enlarges the tale and expands the space of the image. We are implicated, if we stand in its range, in the universe of the story.

Dennehy is that figure, with a difference, in THE ICEMAN COMETH, the play that stands just behind Long Day’s Journey Into Night as Eugene O’Neill‘s culminating achievement. Dennehy’s Larry looks outward in the way that those who in reality are looking inward, at some private preoccupation, do. Preoccupation is always about the future, and Dennehy gazes, not on a present event, or person, but on the death he longs for but will not, for some niggle of sentiment, bring upon himself. He is tired of living and afraid of dying (O’Neill sets the play in 1912 – “Old Man River” was written in 1927), “barker for the big sleep” (Chandler ‘s novel came out in the year, 1939, that the play was written), done with life, a dying rebuke to the American Dream that, lest we forget, wasn’t named as an ideal until 1931, at its moment of greatest impossibility. Dennehy sits, the familiarity of his features stony on a Rushmore of despair, such that, when he hobbles, a broke thing, to the bar, it is like the limp of a dream – Hughes’ “broken winged bird” – pitiful as a nightmare, a sad old man looking for the guts to die.

No one in the American patriarchy, even the Arthur Miller of Death of a Salesman, is a greater poet than O’Neill of the pain of men. Miller thinks we don’t deserve it. Something in O’Neill feels that we do. Yet for the condemned among us his sympathy is infinite, while Miller, on some level, is unforgiving. We are presented in ICEMAN with a stage full of drunks who stay with us, silent, talkative, resigned, self-pitying, lonely and companionable, for the better part of five hours, counting the intermissions. The attenuation of time, with a purpose, is another thing that O’Neill does well. He pulls us, against all odds, into trance; at least he does with actors this good; all in order to say that we are in another, longer kind of trance, and have been so in this country for years; no: generations; which history can’t be counted on, nor politics, to snap us out of. ICEMAN and Long Day’s Journey are set at the start of the 20th century, but, written mid-century and performed today, abrade us with all that hasn’t changed in American life, from the deceitful banality of commercialism, to the ethic of success and the shame of failure, to the prison bars of disfunction and the lies that weld them, to race, the wound that reopens whenever it seems, finally, to have started to heal. John Douglas Thompson as Joe, “one-time proprietor of a Negro gaming house,” makes that point all too well in the production’s most scorching scene, an outburst of bitterness that roused all who could relate to it in the BAM audience to applause.

Against the taciturnity of Dennehy’s Larry is set the loquacious Hickey of Nathan Lane, an icon of glib American self-helpery if ever there was one, puncturer of dreams and peddler of hopes even falser. There is something a little false in Lane’s performance too – including in Hickey’s great, extended fourth act monologue – but then again maybe there ought to be, for the point is that the man is a fraud. Awaited like a savior, he arrives sober and monied, but leaves the worst sort of object lesson, without so much as a life to look forward to. His exit draws the focus of the entire stage, packed with the whole sprawling cast (each of whom would deserve mention were it possible to do so). It’s one of the sharpest delineations of attention I’ve seen in the theater, the crowd is so singly focused that if you drew lines from the tips of each of their noses they would converge on an exact point in the wings, a hundred feet away.

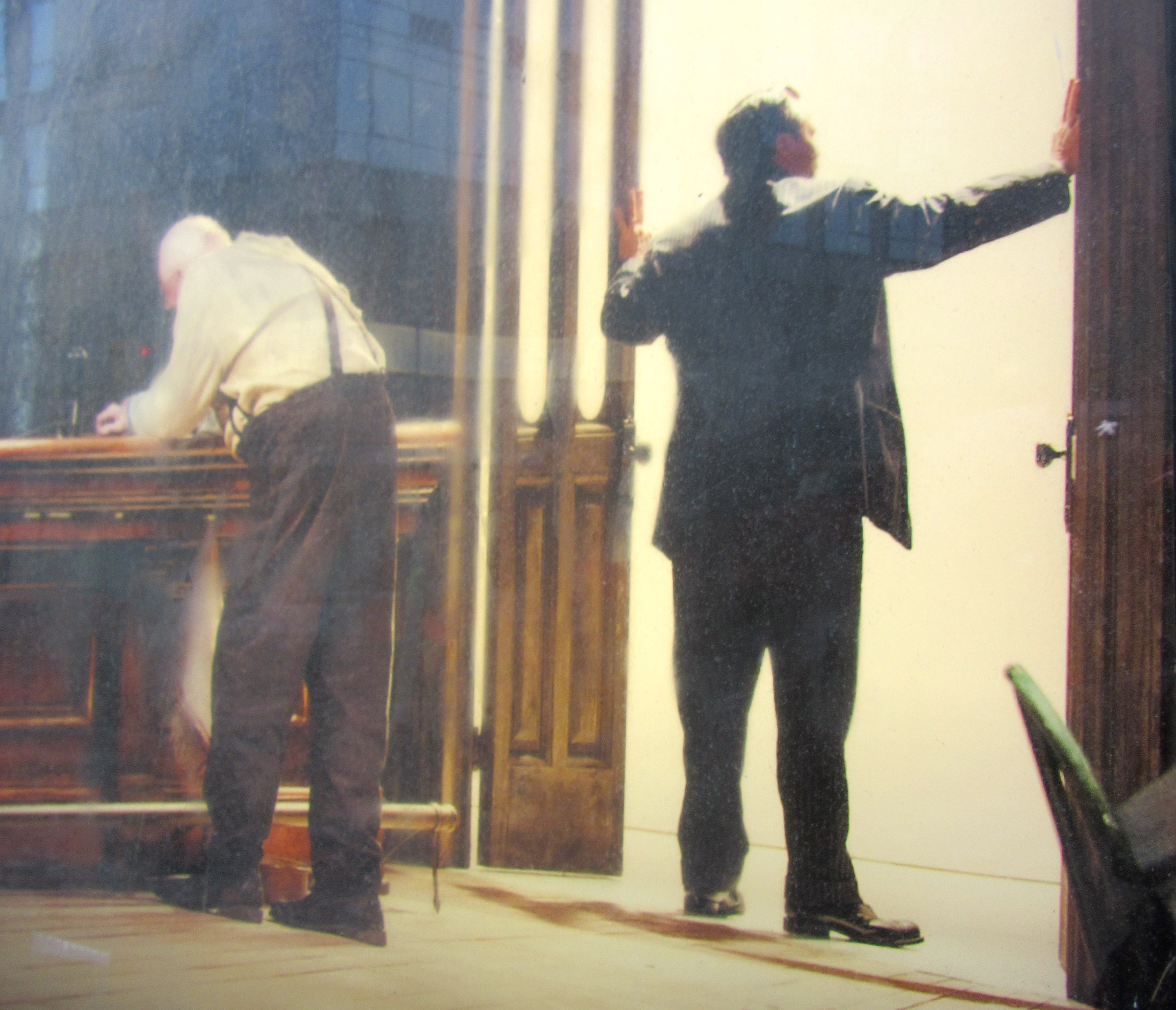

It is, like so much in this production, both dynamic and pictorial. The director Robert Falls, with his stage compositions, and the designers Kevin Depinet, John Conklin, Natasha Katz and Merrily Murray-Walsh, paint, on four successive sets, a living picture of American despair. Imagine the interiors of Hopper populated by a defeated crowd and you get some sense of the desolation it conveys. Not that there isn’t, in the imagery, the occasional glimmer. The set for act three is particularly brilliant in its manipulation of perspective; the planks of the floor come at you like a sunburst from the daylit door. It’s temporary. By the next act, dominated by a high window on an expanse of wall, we are in Beckett’s Endgame. The associations with 20th century existentialism that ICEMAN, and this production of it, invite are legion, starting with the waiting: for Hickey, death, the iceman, the end to come.

All the while there is the figure cut by Dennehy in the picture, the gazer on some bleak hope of oblivion, just a little past the rear of the theater. He does walk around a few times, of course, and seems shockingly frail: the terminal hunch, the sciatic limp. He stays in character for a good ways into the curtain call, to a point that it is almost worrisome. Then, to the death’s head of his skull, a smile finds its way, and the flesh fills it out again.

For information about programs and events at BAM, click here.