The art of the stage is largely one of clearing space, of getting impediments out of the way and avoiding the incursion of new ones, demarcating fields on which patterns of experience emerge through time, be they psychic, spiritual, or ideological. A new lushness can take root, or a greater austerity.

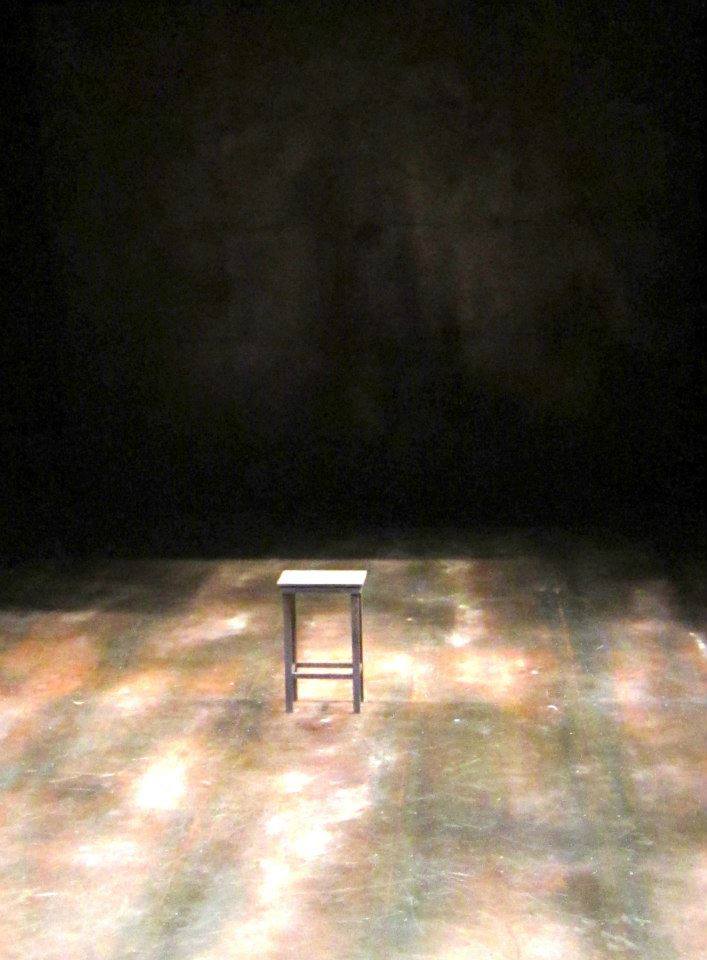

Or both, as they do in the beauteously sparse KING LEAR that Arin Arbus has directed at the Polonsky Shakespeare Center. The décor by Riccardo Hernandez is little more than a floor and a hinged wall; it is textured like rusted steel; and the only set pieces are a podium, a stocks, and a chair. As the tragedy deteriorates, Susan Hilferty’s costumes do as well, whether they are bloodied, dirtied, doffed for nightwear, or turned to rags. Until then, the beautifully constructed gowns of the women, with their high collars and ankle length skirts, stand out elegantly on the oxidized set. Arbus has orchestrated a world of beauty but not prettiness; tragedy but not melodrama; comic relief but not silliness. The density of Shakespeare’s text is delineated with great clarity, with its foils, archaic cosmologies, and teetered balance between tragedy and the comic. There is nothing, in either the staging or the acting, that adorns without illuminating. As Gloucester, whose eyes will be popped out of his skull, the actor Christopher McCann is given one of the production’s rare props: a pair of reading glasses.

Even the casting of the lead reflects a stripping down to the telling and necessary. Michael Pennington is a distinguished actor, known and respected here and in England, but not, at least stateside, a celebrity. He builds his Lear like a craftsman, then has the courage to let him go to pieces: this is a Lear who fears going mad, which is to say that he fears the fact of death in the world, his own and of those he loves. The tenderness with which he falls apart, the bleached beatitude of his sorrow, is as moving a thing as I have seen in the theater. We are not, however, meant to feel sorry for him uniquely. The old king in Arbus’ vision is one whose actions, although they do not merit the fate that befalls him, cannot be defended. It is not just his hubristic anger at his youngest daughter for refusing to exaggerate her love. Lilly Englert’s strong-wistful Cordelia is, in fact, no saint; her demurral is itself a kind of hubris, a too-righteous rejection of conventional niceties. It is also the insensitivity of the demands he makes upon the daughters in whose favor she is exiled. Bianca Amato’s Regan and Rachel Pickup’s Goneril, contemptible though their actions are, are not unvarnished villains. Amato is, in particular, darkly persuasive in her condemnation of Lear’s arrogance and in the peace offering she makes him.

It is a remarkable moment, highlighting how important it is, in the experience of this Lear, that Lear’s heirs are daughters instead of sons. Would he have exiled a son, or declined a reasonable compromise offered by another (merely to trim his entourage, after all)? Somehow we sense, without it ever being stated, that he would not have. We are reminded in the midst of a drama that is fundamentally existential of the power relations that distort our ability to answer, or even to ask, the great questions that it poses. Sorting out those relations, Arbus’ LEAR suggests, is a necessary step to the latter.

Visit Theatre for a New Audience for information on events at that venue.