It is particularly true of Shakespeare that his individual works both feed off and nourish an entire body-of-work. Hamlet is the richer for Macbeth, Twelfth Night for King Lear, the comedies for the tragedies, Falstaff for Toby Belch, Viola for Sonnet 121 and even for Iago. In LAST LIFE: A Shakespeare Play by Sara Fay George at Box Collective, currents from the many works eddy in a rapturous contemplation of love and its discontents: phrases, passages, poems, and pieces of dialogue are extracted and re-arranged like themes in a fantasia. Even those that don’t speak explicitly of love, but of death, human nature, or justice, elaborate upon it, as though it were the ocean bed of all else.

LAST LIFE proceeds as ritual within a circle of salt. Khadija Sallet – the figure of Kismet (or fate) – pours out the white grains as she sings “The Phoenix and the Turtle,” with its implications of death and rebirth. Inside the circle are a woman and a man, prone, who are unable to leave it and whose love will live and die in an hour, with ups and downs and bursts of passion and conflict; it has happened before and will happen again, as the words have been said before and will be again, in innumerable spaces, by countless others, friends, lovers, countrymen, and women.

Man and Woman stir, and they encounter each other, like amnesiacs who have forgotten their lives together. Esther Sophia Artner’s eyes open with wonder when she sees him (Mikaal Bates), pools of unplumbed depths. Later they will glisten with tears and look with the precision of a hawk into the distance – at thoughts or some unknown thing. Her lithe physicality unites body and voice; she speaks the Shakespeare firmly and without strain; meaning is lodged in the shape and softness of her breath. Bates, shirtless, I saw first from the back, his muscles painfully defined (to those of us whose are not) and expressive in their own right, tautening and turning pink in response to tension and high emotion.

George directs as well as writes – on the script available at the event, she is said to have “composed” it. Merchant of Venice, The Taming of the Shrew, All’s Well That Ends Well, Much Ado About Nothing, Romeo and Juliet (of course), Henry V, Hamlet, Twelfth Night, and, I think, Antony and Cleapatra are there, and more. There’s a natural tendency, if you know Shakespeare, to recognize the lines and try to place where they are from. But George’s composition is so graceful and the performances she elicits so subtle and coherent that the recognition game is more about unexpected connections and flashes of insight than testing one’s knowledge.

Hamlet’s “What a piece of work is a man” is said once as written, them glossed to say the same of “a woman.” It is the only edit that stands out a little, not because it is overtly feminist, but because the rest of the play’s feminism is deep, pervasive, and fundamental. George and her actors (especially Artner) give surprising credit to Shakespeare as a portrayer of women and a conduit of their desires. George goes so far as to say in her preface to the script that he was the first feminist. It’s as though the profoundest poetry is progressive in its depths, no matter how hegemonic on the surface. LAST LIFE is a dialectic of love in which even The Taming for the Shrew has its point on the pendulum swing; the problematics aren’t ignored – indeed, they hit hard – but neither are they reduced to ideology. Woman and Man love, want, struggle – fight – cyclically, in an eternal but ever progressing return.

This is a questioning, constantly searching piece of work. Viola’s great “I am not what I am” exchange with Olivia links the shifting sands of identity to the mystery of who one loves and why. But LAST LIFE has a core, a belief or an aspiration (at least) in the centrality of love to human fulfilment. The words of the “marriage of true minds” sonnet (116) connect love, with absolute fixity, to existence itself, a context in which I missed Othello’s “Perdition catch my soul/ But I do love thee! And when I love thee not/ Chaos is come again.” Or perhaps it was less missed than brought to mind, as, when Artner first sees Bates, is Miranda’s “O brave new world,/ That has such people in ‘t.”

This is the third iteration of the play, which feels, appropriately, like something that will always evolve, like a living being. A previous title, in productions at the New Ohio Theater and a Shakespeare conference that I didn’t see, was 116, after the sonnet. Perhaps “Last Life” implies that Woman and Man have reached the seventh and last age of which Jaques speaks in As You Like It. Or perhaps they will start again, eternally, at the first age, the infancy of love.

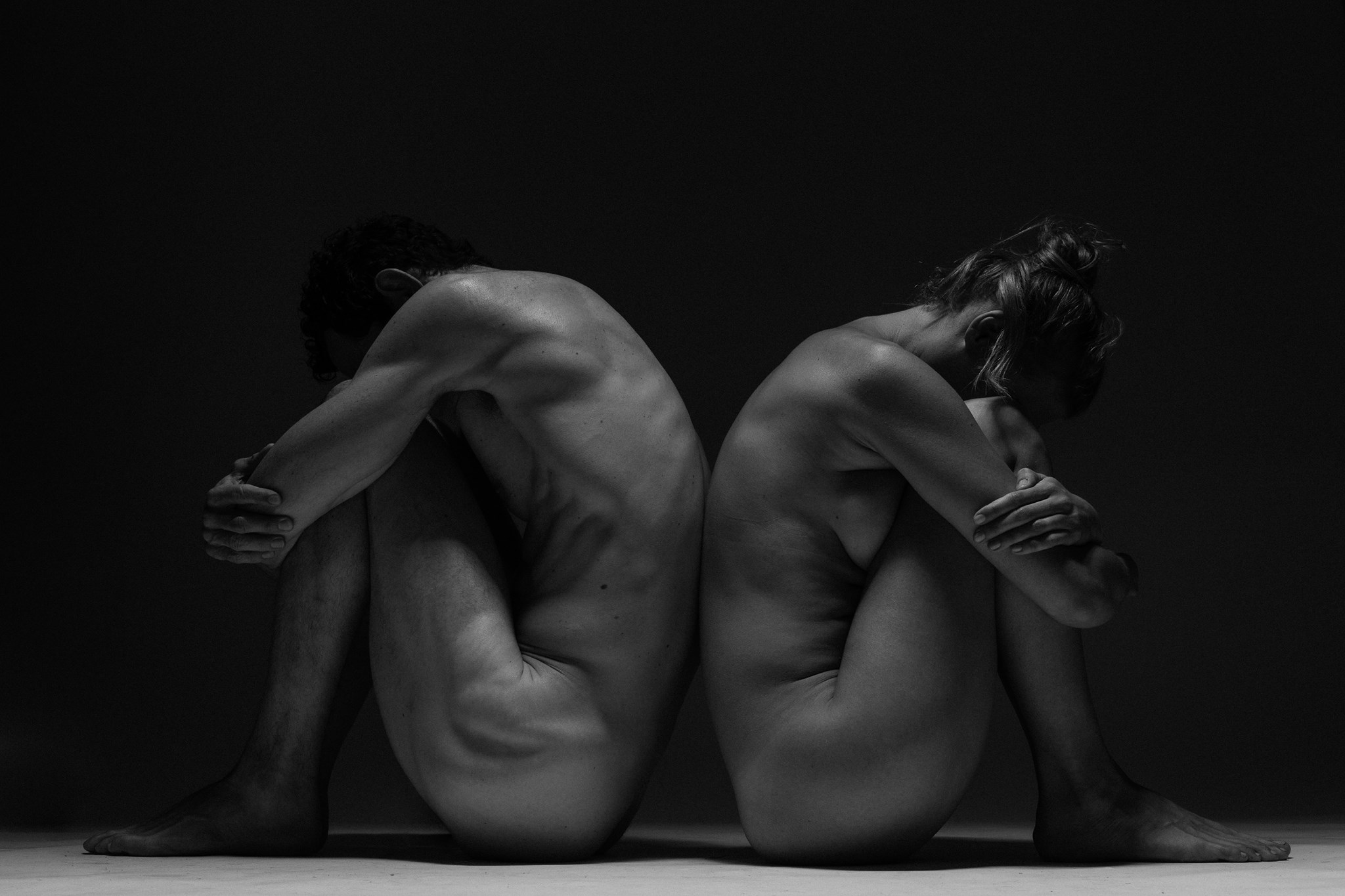

Kismet sweeps away the salt, but the experience continues. In the lobby is a photography show by Theik Smith of beautifully composed black-and-white nudes of the principals that are both past and prologue to the play.

LAST LIFE by the Box Collective plays at Loft 29 through June 30, 2018. For information and tickets, click here. Photo: Theik Smith, shared image from the lobby exhibit.

One response to “Last Life”

[…] I wondered if this isn’t a motif for the Box Collective: the other of their shows I have seen was a pastiche of Shakespeare performed in a circle in which the main actors descended to the floor to enact a dance of gender identity. Sara Fay […]