When Malcolm says of Macbeth’s grief after the discovery of the murdered Duncan, “To show an unfelt sorrow is an office/Which the false man does easy,” it is in contravention to the late king’s lament on the execution of the traitorous Cawdor that “There’s no art/ To find the mind’s construction in the face.” No art, perhaps, but Malcolm has the instinct for it, and it was when he said it that I understood what Kenneth Branagh might be getting at in his MACBETH, which he co-directs (with Rob Ashford) and stars in at the Park Avenue Armory. It keyed me into that, but also into what was not always satisfying about an admittedly thrilling experience.

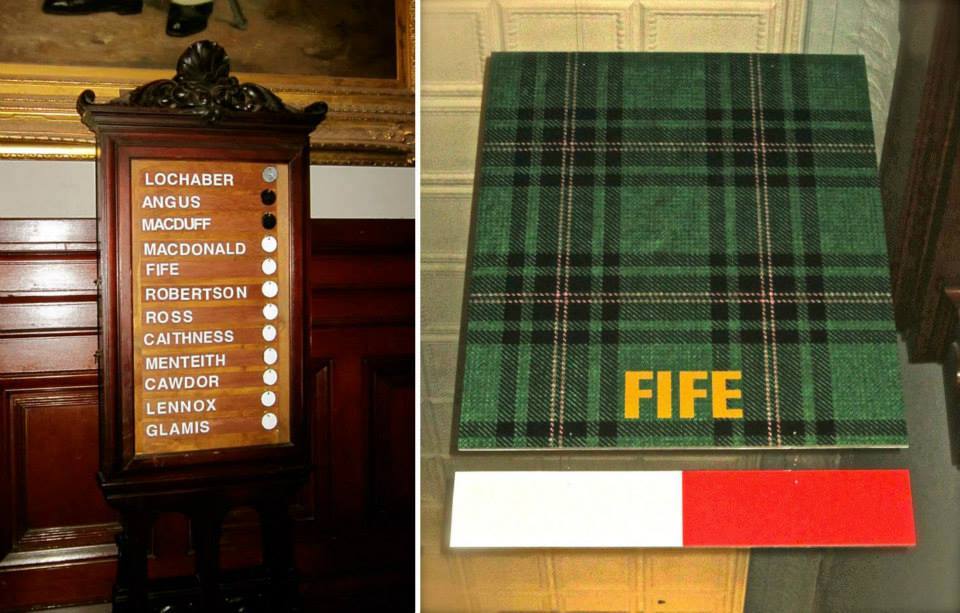

The mustering of the audience into clans, the blasted heath they cross to reach their seats, the sight, once there, of other clans being led by torchbearers over the expanse, the peaty surface of the playing area, in which footprints and drag marks are actually left, are all quite something. The three witches flit about the stage a little too often, and the whole thing is a little theme-parkish, but why, really, resist? The acting is predictably solid overall; the standouts for me were the moment when Alex Kingston, as Lady Macbeth, draws a circle in the soil and summons the spirits to fill her “with direst cruelty,” and, from his first to last word, Richard Coyle’s vigorous realization of Macduff. But the heart of MACBETH is Macbeth, and it is to see Branagh in the role that so many are making their way to the armory. Even with the reservations I am about to express, they should keep heading there. Branagh’s performance is a double-edged sword that we see before us: revelatory of what might be amiss with Macbeth the character, but also with Branagh the actor.

Branagh is compelling when Macbeth is lying and dissembling, impossible not to look at even amid the spectacle of the production. But when Macbeth has to confront the deepest truths about himself, be they moral faults, existential fears, or emotional needs, he seems to be looking for something he cannot find. He tries desperately to approach the emotion, but reaches it only partly; the “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy, was, at least on the night I saw it, downright halting. Nor did I believe his relationship with Lady Macbeth, even on the level of sexual desire, which he plays up, perhaps to compensate for the emotional deficit. The real fear that Macbeth experiences at the appearance of Banquo’s ghost was not there either. This could, interestingly and credibly, be construed as a view of the character: Macbeth as a man of profound insincerity in ordinary life but of thorough conviction in a world of prevarication and false emotion.

Macduff’s words, which stand out in the staging, give warrant to such an approach, but it meshes – or did at the showing I attended – a little too easily with Branagh’s own shortcomings. There is a long history of anti-theatrical discourse that condemns the stage as a place of falsehood and impersonation, and it is the allure of pretense, and of making others believe it, that attracts a certain personality to the theater. It is obvious that Branagh, a vital figure in Shakespearean filmmaking (especially), loves to act; judging by the zeal with which he feigns and dissembles in MACBETH, he would make a fine Richard III. He gravitates with brilliance to those scenes in which Macbeth himself is, for all intents and purposes, acting. But in those moments when Macbeth is called upon to stop acting and face the reality before him, it seems to go against Branagh’s deepest nature to comply. It is as though his acting has gotten in the way of his acting. He is an actor to the core, and that, at least, is something to see.

For upcoming events at Park Avenue Armory, click here.