SIMON STARLING: AT TWILIGHT documents a revival, by Starling, a visual artist, and the theater maker Graham Eatough, of W.B. Yeats’ At the Hawk’s Well, the 1916 Irish folk play that drew on Noh drama to break with Naturalism and realist art in general. Ultimate reality was, to a Symbolist like Yeats, immaterial but accessible indirectly, through imagery and poetic language. At Twilight revived not just the play but the drama of its creation, the involvement of the poet Ezra Pound, the dancer Michio Ito and the celebrated muse Nancy Cunard, its overlaps with Vorticism, the forest of Winnie the Pooh, and the sculptors Brancusi and Noguchi. Its spirits are both mythical and historical, a netherworld of powers that intrude on our understanding of Yeats and his art.

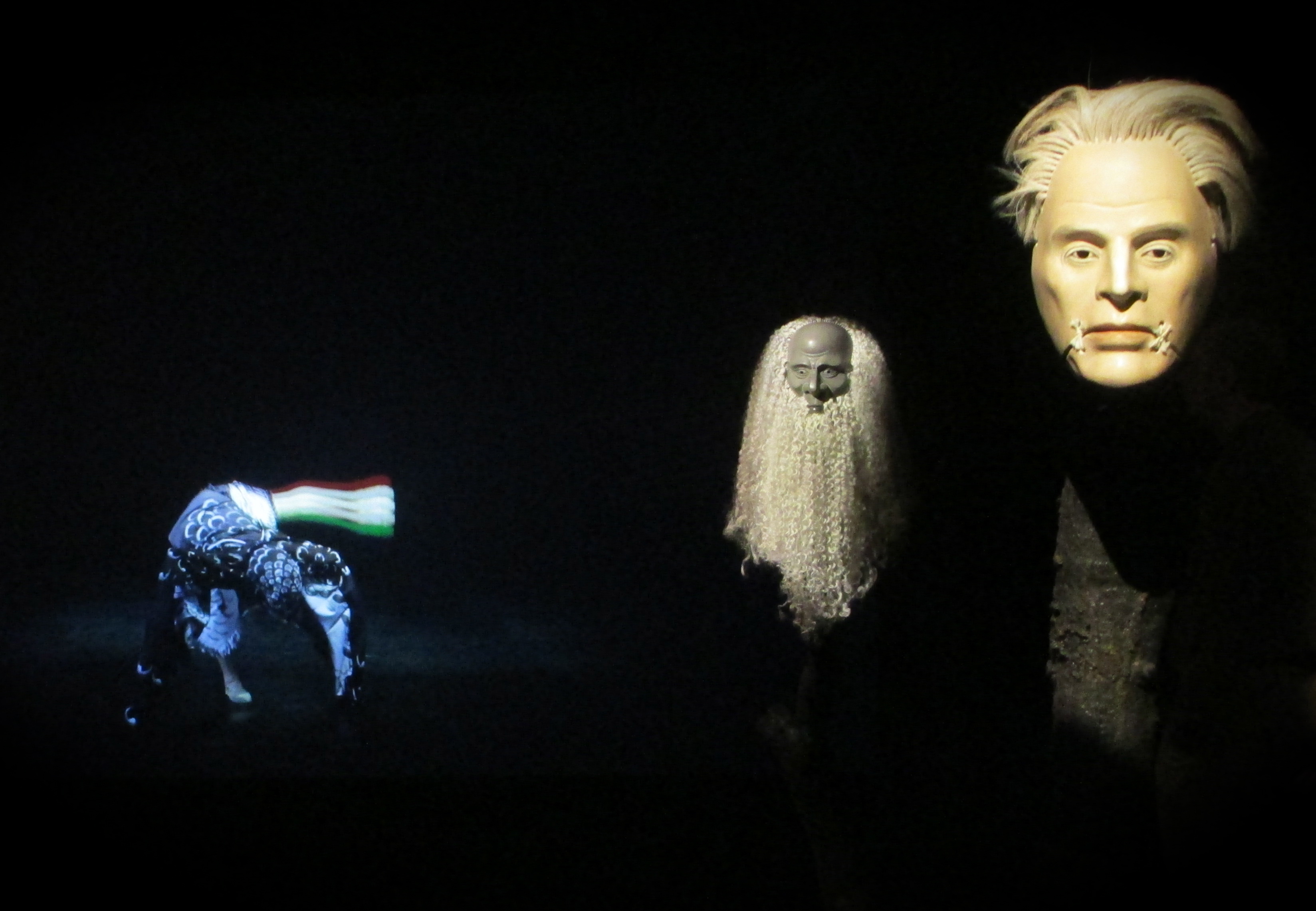

The darkened first chamber at the Japan Society confronts you with At Twilight‘s spiritual ethos. Theatrical masks, dead, uncanny and softly glowing, are impaled on the trunks and branches of trees. The hawk dance from the play, shot in black-and-white, is glimpsed through the illuminated visages. Trees were, we find out later, basic to Starling’s concept, which took inspiration from Yggdrasil, the charred branches of 20th-century war zones, and the bare sentinel of Waiting for Godot. The staging, we will learn later too, took place on the edge of a Scottish woodland, looking and sounding much like Treplev’s outdoor play in Chekhov’s The Seagull (a parody of Symbolist drama). The masks gaze out as though from an arbor of dreams. Yeats’ own is foremost in the line of sight; no actor animates it from behind, but something beyond it does. The experience of the room has an imperious half-life that persists for the rest of the exhibit, which seeks in some sense to explain the material sources of its power.

Japan Center’s galleries are cunningly mirrored and partitioned, expanding the field while focusing the view. The first thing you see in the second room of the exhibit is yourself looking back from the other side, as though interrupted in your (his? her? its?) perusal of the items on display. Reflections, it is easy to forget, are uncanny in their own way; it is odd to see yourself in a space before you have entered it or in one that, unlike Alice, you cannot enter. Between the two of you lie the carcasses from which the heads in the other room have been detached, a donkey suit, the wings of a hawk, capes and garments. The lighting is ordinary: soul doesn’t clap here as it did in the forest. These are costumes, interesting to see, but only that, an artful shift, in the organization of the exhibit, from installation to archive.

There are two more rooms to pass through, the first a hall of documents, sketches, photographs, a sculpture or two, the stuffed donkey, Eeyore, from Winnie the Pooh, and superb curatorial placards that link the items together. A video documentary of the August 2016 production is shown in the final room, and an informative catalog (worth the purchase) expands the picture further. It is as though Yeats’ play has accumulated meaning in the hundred years since its premiere. In SIMON STARLING: AT TWILIGHT it bears much of the history of art in the 20th century on its gnarled and re-grafted limbs.

SIMON STARLING: AT TWILIGHT continues through Jan. 15, 2017, at Japan Society. For information, click here.