Things are ironically prominent in the THE CHERRY ORCHARD brought by the Maly Drama Theatre of St. Petersburg to the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Most of the action happens on a pile of household possessions, much of it covered in white sheets, at audience level, in front of a stage blocked, most of the time, by a projection screen. Even the seats in the audience (although not in the gallery) are covered by linen throws, and at the back of the house a mysterious piece of machinery – that turns out to be a movie projector – is also draped. As for the persons of the play, they huddle, at key moments, atop the things, looking like things themselves, refugees, they might be, on a cart with what little they have salvaged.

None of which endows the things with much meaning: the usual paeans are delivered to them, but they are really just stuff, more like the wares of an antique shop that fit together visually but lack a common history. Even Lyubov, the returning matriarch, doesn’t care that much about them. The estate is a place she has been dragged back to, lovelorn and broke after a Parisian sojourn, not one she wanted to return to: her memories are perfunctory, like lines remembered from a sentimental drama, kneejerk nostalgias that Ksenia Rappoport, in a fascinating performance, delivers in a state of what-else-am-I-supposed-to-say exasperation.

The Maly understands that Chekhov portrays the ways that people read meaning into things rather than fixes them as literary symbols. The image that is important enough to give the play its title is chopped down at the end for cash, just as the titular symbol of The Seagull is shot, stuffed, forgotten and absurdly taken to heart. Still, I’ve not seen a Cherry Orchard that so strips the estate of its sentiment, not merely as a whole, but in the minds of its denizens. The home movies that are shown (somewhat anachronistically – the play is set around 1900) are more enduring than the goods stacked before the stage, images as dematerialized as memory itself, yet preserved and carried away, at the end, in a tin. The orchard was never the ground of the household’s existence, only the last remnant of it. The carpet was pulled not with Lyubov’s spendthrift ways but with the end of serfdom decades earlier, as the ex-serf Firs, bemoaning the liberation of his class, reminds us. Woodchip by woodchip, the economic basis of the homestead has been ground to a stump.

Lev Dodin’s direction finds a materialism in Chekhov that interacts with the metaphysical yearnings of the characters, leaving undulled the sheen of their conversation and the music of their interaction. The strange sound that twice in the play sends a chill down their collective spine is recognizably a warning siren of some sort. Its impact, nonetheless, is strange and unsettling: in context the sound makes no more sense than the distant harp string of the original, perhaps less. It’s one of several liberties Dodin takes, with time, place, incident, and language, and all but one work just as well – the exception stands out a little painfully: fortunately the play rights itself quickly thereafter.

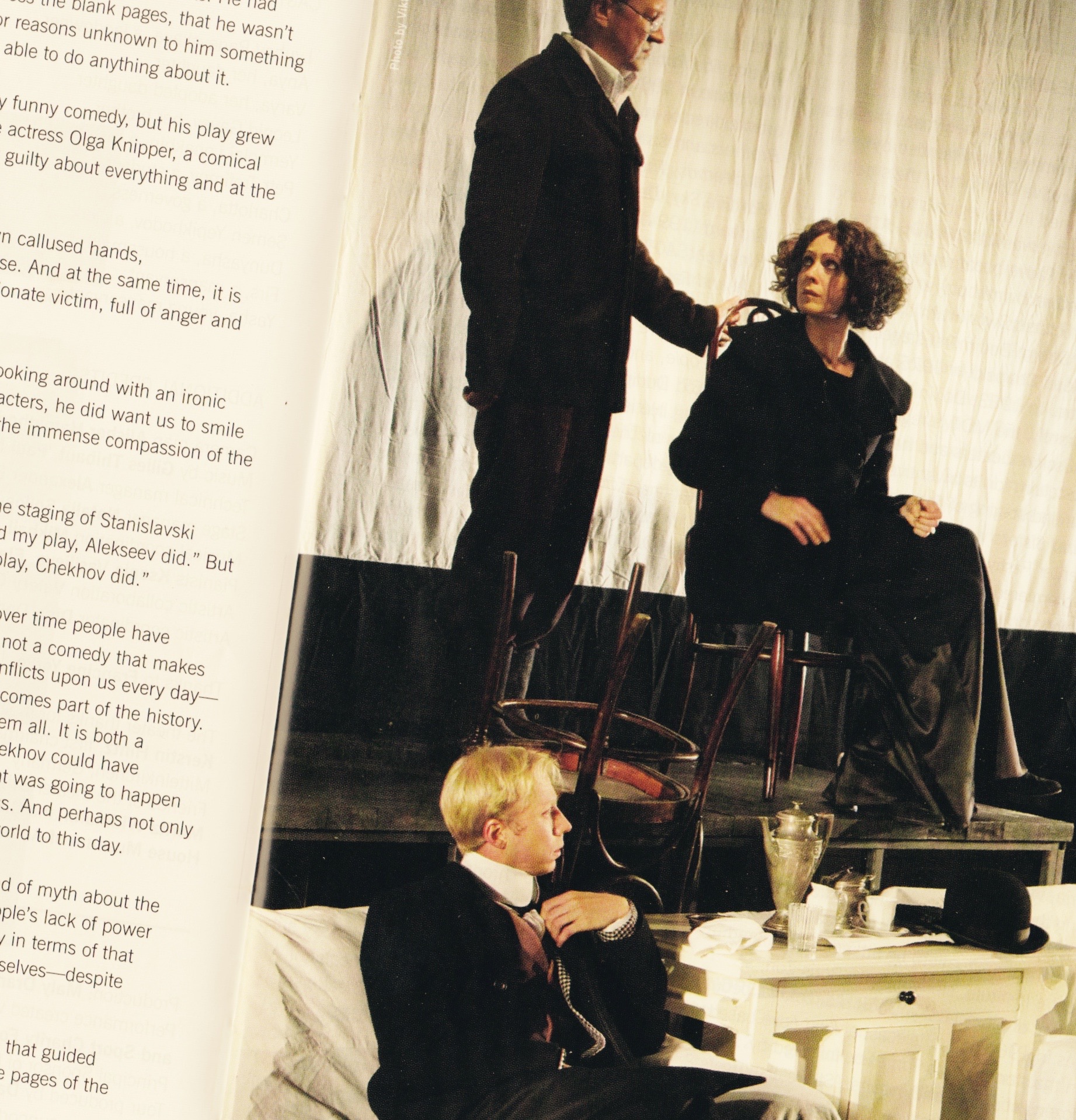

The actors capture the human reality that even the most clear-headed and emotionally in control are buffeted by desire, uncertainty, selfishness, love, and contradiction. Rappoport, hair coiffed like wings ready to take flight, arms shooting up in repeated dismissal, redefines Lyubov as one whose only nostalgia is for the wherewithal to leave it all behind, once and forever. Her daughter Anya is played with smart elegance by Danna Abyova, and the adopted Varya, on whom a cruel hurt descends, by Elizaveta Bolarskaia with an ennobling strength. Arina Von Ribben makes of Dunyasha, the housemaid, the life force of the estate and what will come after its sale. Andrei Kondratiev and Oleg Ryazantsev find perfect balances between type and individual as the clerk Yepikhodov and the eternal student Trofimov. Danila Kozlovsky’s Lopakhin, the proto-capitalist with his eye on the orchard, is cynical and visionary by turns, his charm oleaginous but outgoing.

Igor Chernivich, Sergei Viasov, Tatiana Shestakova and Stanislav Nikolskii round out the household, almost. It is Firs, of course, who closes the circle, at start and finish. He is, in Sergei Kuryshev’s portrayal, the most nakedly symbolic figure in a world of emptied things, and also the last, the soothsayer run out, finally, of truths to tell.

THE CHERRY ORCHARD continues through Feb. 27, 2016, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Click here for information.