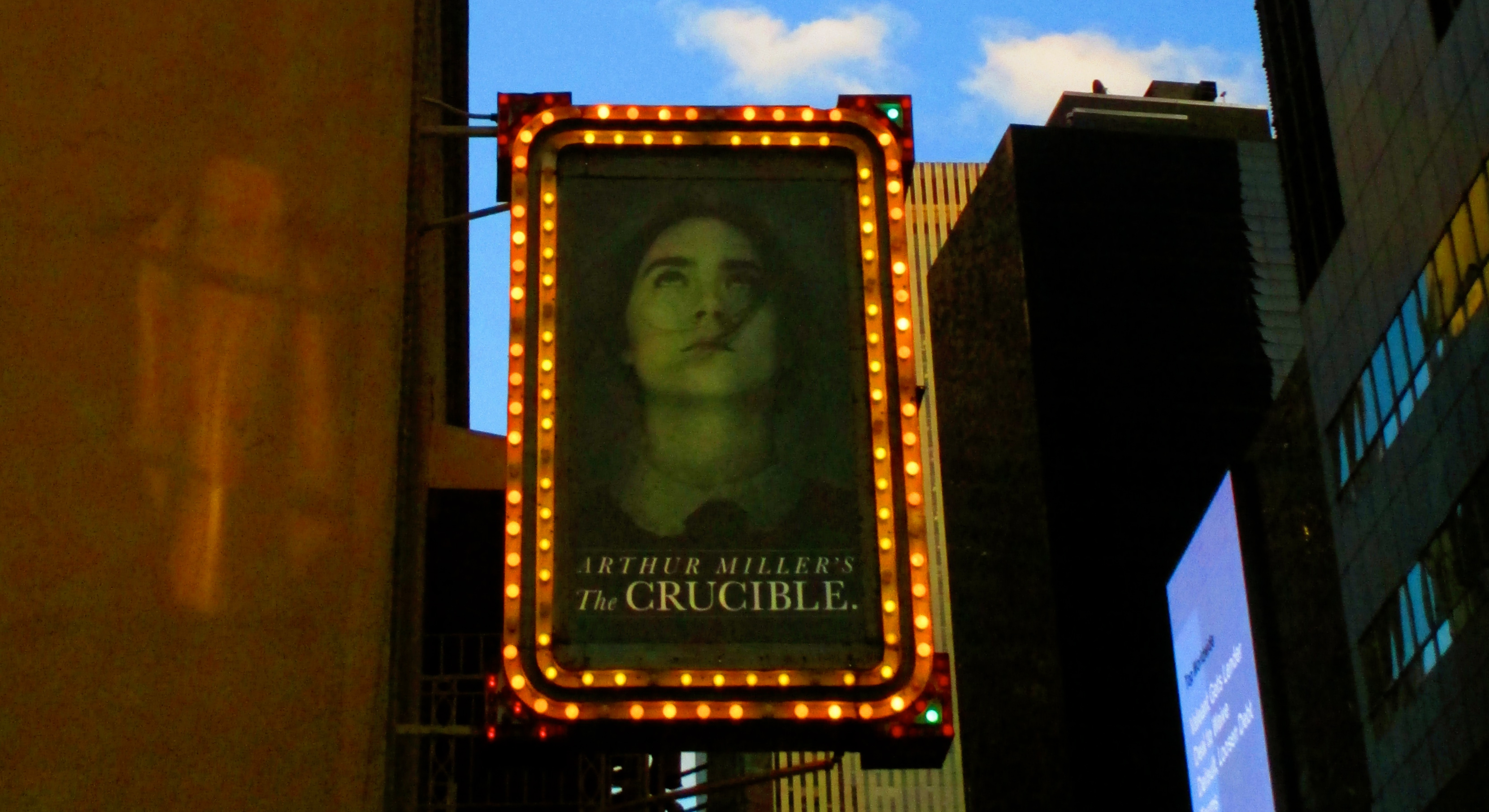

The director Ivo van Hove has turned his eye on THE CRUCIBLE, Arthur Miller’s treatment, in 1953, of the Salem witch trials as analogous to McCarthyism. Van Hove’s version begins, as did his A View from the Bridge, also by Miller, with a black scrim interposed between the audience and the playing area. No – it starts sooner, actually, with images of Saoirse Ronan plastered all over New York, bracketing the entrance at the Walter Kerr, and lowering overhead. She isn’t black-and-white, more a sickly green, like air after a lightning strike. It’s an aesthetic right out of Japanese horror, as though something in her is dead, but something else too much alive. Inside, when the scrim goes up, we see that the stage, too, is drained of color, all the more by contrast with the black. The chalkboard (for what we are looking at is a modern schoolroom) sets the color palette for the whole; an amber wash, high on the back wall, only accentuates the general paleness; it’s a world of people like fever victims, bled to a cure by a medieval doctor.

There are also problems with the electricity (a light fixture blowing out) and an explosion, with no obvious cause, that peppers the stage with debris. It feels as though something otherworldly is happening, which raises a question or two relative to the play’s core factual premise: the falsity of the witchcraft allegations made by a group of young women against a growing circle of Puritan townspeople. To be sure, concomitant supernatural events wouldn’t mean that any particular accusation was true: the antic dispositions of the young women (who claim to be supernaturally tormented by the accused) could still be attributed to guile or the power of suggestion. But while the strange phenomena aren’t used as evidence of witchcraft per se (they aren’t commented on), we – who are the ultimate jury – see them happen, and it complicates the assumption, on which Miller relies heavily, that the accusations are not only false but, in a materialist world, impossible.

How to interpret this odd credence given to the supernatural? Is it a misstep, albeit theatrically compelling, given the difficulties it presents? Does it deconstruct the received view of Salem as an irrational outburst, subtly questioning the scientism behind it? Might it challenge the audience not to be too judgmental, as we too can be fooled, and regularly are, by special effects? Could it portray, in a metaphorical way, the power of the collective mind, a sort of telekinetic marshaling of false witness, mass delusion and “private motive” (more on which later)? Is the point to make one question what is happening, even the appropriateness of van Hove’s choices, such that doubt becomes an active part of the experience – as it was not in the spectacle of McCarthyism?

All doubt aside, the result is compelling. Ben Whishaw and Sophie Okonedo are John and Elizabeth Proctor, whose lives are torn apart by the false accusations, made by Abigail, the 17-year-old with whom John had a short, and intense, liaison. Whishaw and Okonedo’s chemistry is deep, and conveys a profound love; it is redemptive merely to watch them. Ronan, as Abigail, is hypnotically present, with eyes that cut and a stillness that, when called for, gives her a subliminal power. She seems halfway between sleep and waking, with the unsettled intensity of a dream: the hold she has over the young women is all too credible. It is Tavi Gevinson, as Mary Warren, who most struggles to free herself. The bond with Abigail tightens, in Gevinson’s performance, like a band of rubber, after a deceptive loosening, and snaps her back. Watching the tragedy transpire, Bill Camp, as the Rev. Hale, captures the troubled helplessness of one with the status to speak but no power to act or decide. In Ciarán Hinds, as the implacable Danforth, under whose justice the accused fall, one feels a perverse integrity, his mind narrowed to the circular logic of a decision already made.

This is van Hove’s fourth staging in New York this season. We have seen his Antigone, with Juliette Binoche, and his Lazarus, the David Bowie musical. His A View from the Bridge was epochal, a revindication of the nature and potential of theatrical experience. THE CRUCIBLE widens his engagement with Miller in an arresting way, yet, as was true of A View from the Bridge, something in it nags, due precisely to the rigor of the direction.

I saw, in the savagely exposed space of A View from the Bridge, no dignity due, despite Miller’s evident intent, the protagonist, Eddie, whose possessiveness and sexual insecurity (centered on the niece he raised as a father) results in a spilling of blood. The same pattern stands out, as things do with van Hove, nakedly, in THE CRUCIBLE. It is at base the drama of a man, Proctor, upon whom a spurned woman takes a terrible revenge. McCarthyism was undoubtedly colored by private motives, but what Miller desires, again, is to tragically redeem a male protagonist who has committed a wrong against women. THE CRUCIBLE goes so far as to demonize (almost literally, in van Hove’s hands) the one he most used and threw aside. Van Hove’s uncompromising theater doesn’t allow, wittingly or no, so uncomfortable a tendency, even as it relates to an iconic writer, to go unnoticed.

THE CRUCIBLE runs through July 17, 2016, at the Walter Kerr Theatre: info.