It is tempting to attribute the visual elegance of THE LIBRARY to the fact that it is directed by the filmmaker Steven Soderbergh. And in some ways the production at the Public Theater does have a cinematic feel. The frame defined by the proscenium is, to the eye, a perfect rectangle, its corners sharp and unsoftened, and there is a certain flatness to the imagery, making the human figure stand out from the background with a clarity that is both beautiful and abstract. This owes much to the rich, colored washes of the lighting designer David Lander, which progress in successive scenes like the stages of a particularly gorgeous sunset. There is, however, a verticality to the visual field that comes slowly into view and counters the effect of two-dimensionality. The floor and side panels are polished to a gleam, and the reflective surface on which sit the tables and chairs of the set (Darron L West and M. Florian Staab, designers) extends their legs to an imperceptible depth. THE LIBRARY may, in other words, benefit from the eye of a director accustomed to two-dimensionality, but, with the depth of a shadow play and the profundity of a mirror, it is much more than a cinematized stage play.

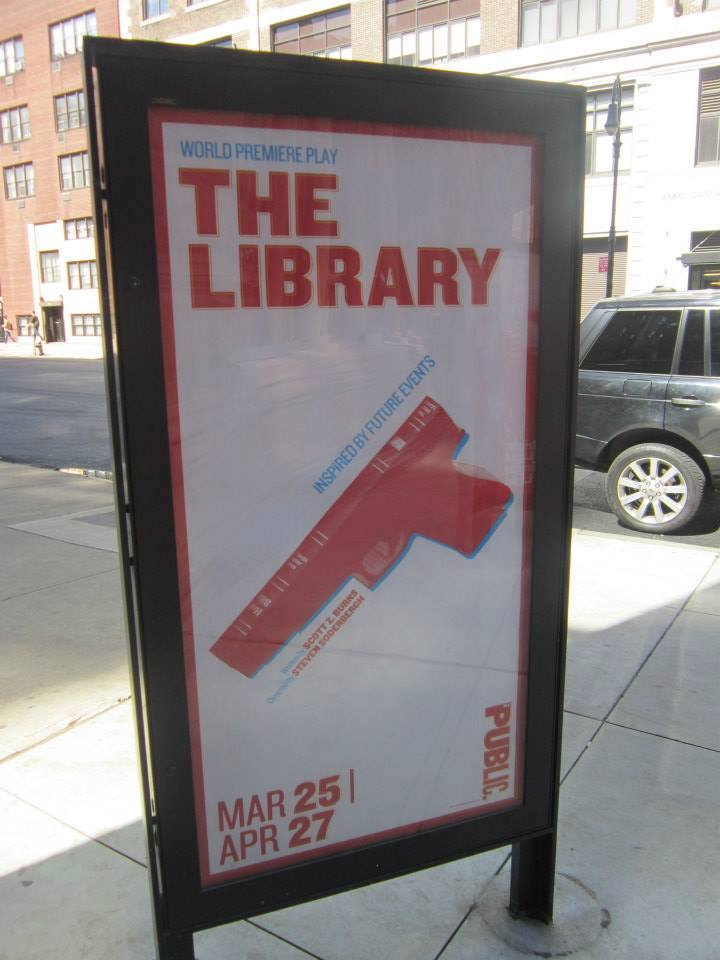

Its complexity as a visual experience fits well with Scott Z. Burns’ RASHOMONesque script, which sets two or three versions of a mass shooting in a school library in opposition to each other. Did the central figure, a student named Caitlin (Chloë Grace Moritz), tell the killer that a group of her classmates was hiding in a cabinet? Or was it someone else, perhaps even the daughter of the pious Dawn Sheridan (Lili Taylor), who has been lionized in the press for praying in the face of the gunman who took her life? Will the question be answered, or left hanging, and what exactly will or would be the moral import of the answer? We have in this play a killer we never see, who indulged a fantasy of fame through infamy; an heroic figure, Sheridan’s daughter, who achieves fame for her piety; and a young woman (Caitlin is, surely, a girl no longer) who is more infamous for her alleged revelation (and, if the allegation is true, act of self-preservation) than the murderer, who, by comparison, is all but forgotten. Moritz and Taylor are compelling in their individual ways; one expects this from Taylor, too often forgotten in the roll call of our best actors; of Moritz, I did not, having missed her film and television appearances, have preconceptions. There is, in the event, a convincing earnestness to her, a kind of humility in the face of public scrutiny, even when, as is the case with Caitlin, it has veered into notoriety. This is complicated, relevant, topical stuff, a stew of guns, religion, the media, and personal relations, the last tending to get lost in the mix, as if it were the least, rather than the most, important ingredient.

The aesthetic distance of the visuals, the ironic juxtaposition of flatness and depth, enables a parallel complexity of response, and an openness to whatever truth, if any, is revealed by the end. Tamara Tunie plays the investigating detective in true LAW AND ORDER style, and, may, ultimately, have something important to say. Until that moment comes, if it does, we see ourselves as no more knowledgeable than we logically ought to be, unlike in the real world, when we most likely would have jumped to one partisan conclusion or another, our opinions so fixed as to require a shedding of our identities to change them.

One response to “The Library”

[…] seems to synthesize a dialectic, the resistant Binoche opposite the entitled arrogance that Moritz, an actor of real integrity, bravely takes on. What is astounding, in all of this, is that the film, although self-reflective […]