The aesthetics of the ghost story and of horror in general are essentially those of the Symbolist movement that spanned the 19th and the 20th centuries. Phenomena that are perceived by the senses, say the sight of a ghost or the sound of a raven tapping on the chamber door, intimate the existence of a netherworld, be it Kant’s noumena, Jung’s collective unconscious, or the Oedipal dreamscapes of Freud.

Among literary ghost stories, Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw may be the greatest, in part because it functions on each of those levels. There seem to be real ghosts in it, emanations of a noumenal reality that is normally inaccessible to our perceptions. But James’ nasty little tale also taps into the collective fears induced by such imagery, and is Freudian in its grasp of repressed memory and sexual abuse. It has an affinity with, if not direct influence on, later tales of ghosts and childhood, including films like The Sixth Sense and The Others, and the whole genre of Japanese terror and English-speaking imitations of it like The Ring.

The New York City Opera’s version of Benjamin Britten’s opera of the story – updated to Thatcher era Britain – makes obvious references to The Ring in the flickering ’80s vintage television screen in the living room scenes and the iconography of the female ghost, who might as well be rising up from a Tokyo bathtub. The production has a good, if intermittent, grasp of Symbolist imagery, particularly in the uncanny doll carried around by the young girl (sung by Lauren Worsham) and the Magritte inspired silhouettes of the English gloaming. One of its finest moments is early on, when Britten’s music is at its most ominous and the Governess (sung by Sara Jakubiak) senses before even arriving at her new job in the country that all is not quite well. It is in a much later scene, when the ghost of a very creepy Peter Quint (sung by Dominic Armstrong) sits at the foot of the bed of the young boy (sung by the 13-year-old Benjamin P. Wenzelberg) and seeks to lure him from it, that the horror of what must be haunting the children hits home.

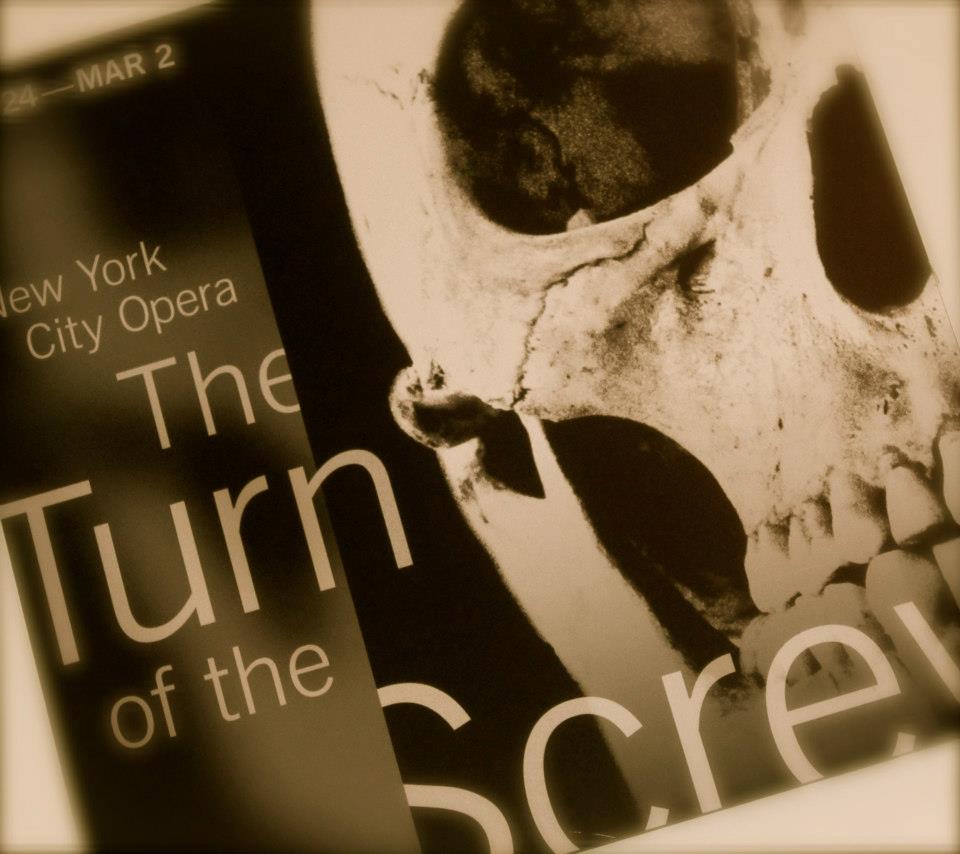

Aside from those two scenes, however, I missed the underlying queasiness that the novella induces throughout; the requisite chills up the spine were also missing; and I wondered if opera as a form, with the inherent unreality of conversation sung and intoned, doesn’t remove the contrast between the familiar and the unfamiliar, the everyday and the intrusion upon it, that is part and parcel of horror – upon the unnatural it is hard for the supernatural to descend. Worth seeing, but not a must see, TURN OF THE SCREW, directed by Sam Buntrock and conducted by Jayce Ogren, continues through Saturday at the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Click here for information on programs and events at BAM.