The title of VILLAGE BIKE comes from British slang for “town slut” or “loose woman,” which is delicate ground to stand – or ride – upon even for a playwright, such as Penelope Skinner, with feminist intentions. But Skinner’s dialogue is so sharply observed, her play so astutely structured, and the cast that the MCC Theater has provided her so humanly convincing, that it never does worse than remind us that some other play might, in dealing with a similar subject, have veered into complicity. It takes someone like Greta Gerwig in the title role to pull this off, and they have her, in one of the most emotionally guileless performances I have ever seen. That her accent slips away from her now and then, and her looks don’t seem to jibe with how the dialogue describes her, makes no difference. She accomplishes one of the most precious of all theatrical purposes, which is to make us look with intensity and forborne judgment upon the needs and desires of a person other than ourselves.

Gerwig has the divided intelligence that defines acting at its best, knowing to a tee the inner life of the person she portrays while simultaneously conveying the confusion felt by that same person as to what is going on inside of her and why. This would, on film, be a kind of voyeurism (as the play’s ending reminds us) but Gerwig’s actual presence has an ironically contrary effect, de-objectifying the woman she is playing and granting her a kind of subjecthood. I have thought from the first time I saw Gerwig in the movies that she was was an actor of uncommon smarts, presence, and emotional truth; she is, if anything, even more impressive in person. The directness with which she conveys the distress of the woman she plays is nothing short of a moral act.

Gerwig is well served by the skill and insight of the playwright: Skinner understands that the great irony of being a unique individual is that there are none among us, no matter how distinctive or original, who are not representative of a larger class of persons – a class defined by circumstance and social reality rather than the sort of stereotype represented by the play’s title. Becky, as Gerwig’s character is called, is of the class that is pregnant, but not showing, somewhere between working- and middle-class, that faces, even in the 21st century, a lingering patriarchy that regards her pregnancy as both a fulfillment of her function as a woman and a license to use her body as a source of pleasure without consequence. That this overlaps with her own sexual desires (shaped by pornographic films whose scenarios are hilariously aped by the situations that arise) is the moral dilemma that Skinner confronts and to which she offers no easy solution.

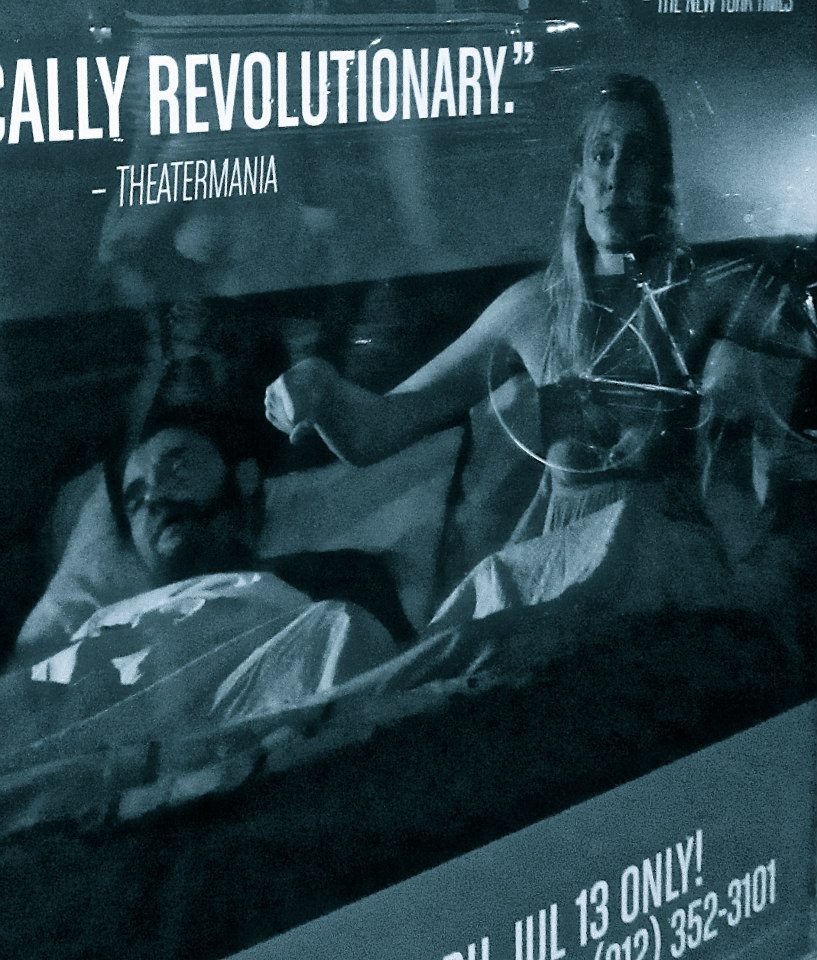

The men of the play represent their own classes of people. Jason Butler Harner, as Becky’s husband John, reacts to his wife’s pregnancy by withholding intimacy while reading books about childbearing and furnishing the nursery. Mike, the plumber who comes by to “fix the pipes,” is given a working class authenticity by Max Baker that, although it doesn’t forgive the way in which he exploits Becky’s body, posits it, somehow, as a consequence of his economic strata. It is Scott Shepherd‘s Oliver, who, owing to his participation in a village theatrical, shows up to sell Becky a used bicycle while dressed as a highwayman, whose behavior is the most hilariously pornographic and ideologically problematic, transforming the private fulfillment of Becky’s desires into an experience of objectification and public humiliation. The sensitivity with which Skinner, and the director Sam Gold, treat this subject matter cannot be overstated; it never veers into prurience, or even anything very explicit; and with Gerwig at the heart of it, what is created is a forum that encourages the profoundest sort of empathy – the sort that makes it impossible to take what happens to Becky as a source of vicarious pleasure and makes us see her instead as a woman of individual value who at the same time reflects an all-too-common state of affairs in our gender relations.

Click here for future events at MCC Theater.