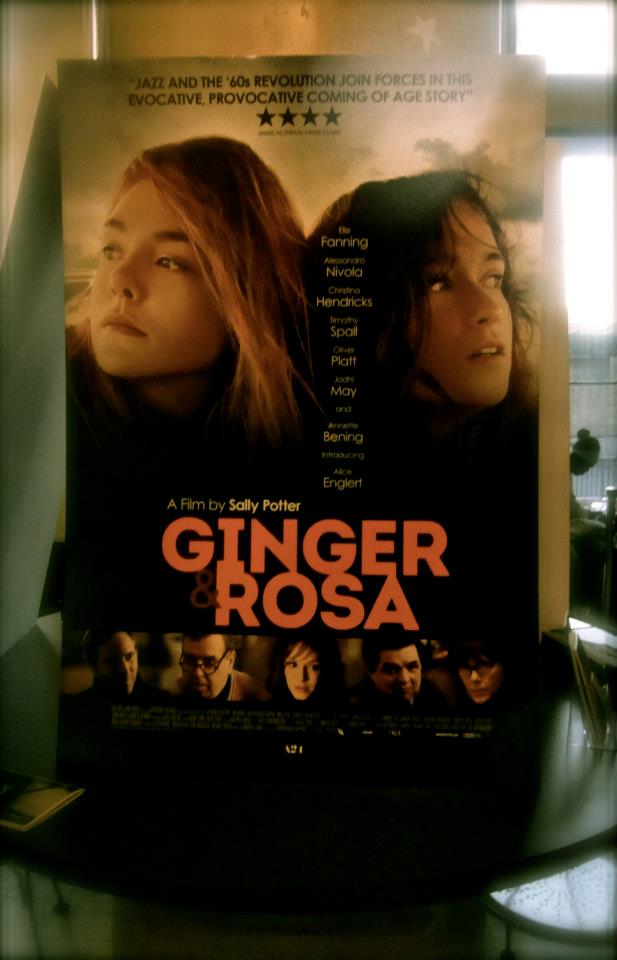

The pleasure I took in Sally Potter’s GINGER & ROSA was deep, and a little quiet, more the sort that I associate with burying myself in a novel than going to a movie. The film felt as though it might have been semi-autobiographical, a portrait of the filmmaker as a young woman, and a cursory Google suggests that was I was probably right.

GINGER & ROSA is, in any case, a British coming of age story about two 17-year-olds in the early ’60s. Their exploration of early adulthood begins fairly normally – truancy, smoking, sexual experience, a retreat from imposed convention into friendship and rebellion. The pair has grown up in a leftwing milieu and meaning is also sought in anti-nuclear activism, framed by the Cuban missile crisis and historical (and slightly heavy-handed) footage of the first atomic explosions. Ginger and Rosa are “twinned”, as the academic jargon would have it, in that they share a birthday and seem inseparable.

But like so many literary twins, they are subjected to a rift that is painful and identity threatening. The truth that they come to is that private needs, desires, and obligations are often more important to the individual than the noblest efforts to benefit the world as a whole. A personal slight, or a romantic betrayal, or basic material needs can loom large at the gravest historical moments, indeed they are, or can feel like, the gravest of all.

Ginger (Elle Fanning) has a father, Roland (Alessandro Nivola), an intellectual whose personal failings are outweighed in his own mind by the rectitude of his politics. Ginger, still unjaded by the hypocrisies she beholds, seeks a middle way between the personal and the political, which is through literary expression and experience. Even at that, she is too young to spot its ironies and moral complexities; she devours T.S. Eliot without recognizing the conservatism at the root of his modernism. This was, after all, the age when, on the other side of the pond, there was a generation clutching Atlas Shrugged in one hand and Herbert Marcuse in the other.

Ginger starts to write, a bit naively, as the filmmaker must have at some point, and senses that by such means she can find a kind of peace in the moral turmoil that surrounds her. I was impressed by Fanning as the younger Potter’s surrogate (or one of them), although I didn’t find her accent work to be as seamless as most reports have had it. There was even greater richness to Alice Englert’s performance as Ginger’s alter ego Rosa, whose personal wants overwhelm the obligations of friendship, which, in this cinematic roman à clef, might well represent an other side to Potter.

Check listings for viewing options.